Oxy: the journey of graceful restarts

Any software under continuous development and improvement will eventually need a new version deployed to the systems running it. This can happen in several ways, depending on how much you care about things like reliability, availability, and correctness. When I started out in web development, I didn’t think about any of these qualities; I simply blasted my new code over FTP directly to my /cgi-bin/ directory, which was the style at the time. For those of us producing desktop software, often you sidestep this entirely by having the user save their work, close the program and install an update – but they usually get to decide when this happens.

At Cloudflare we have to take this seriously. Our software is in constant use and cannot simply be stopped abruptly. A dropped HTTP request can cause an entire webpage to load incorrectly, and a broken connection can kick you out of a video call. Taking away reliability creates a vacuum filled only by user frustration.

The limitations of the typical upgrade process

There is no one right way to upgrade software reliably. Some programming languages and environments make it easier than others, but in a Turing-complete language few things are impossible.

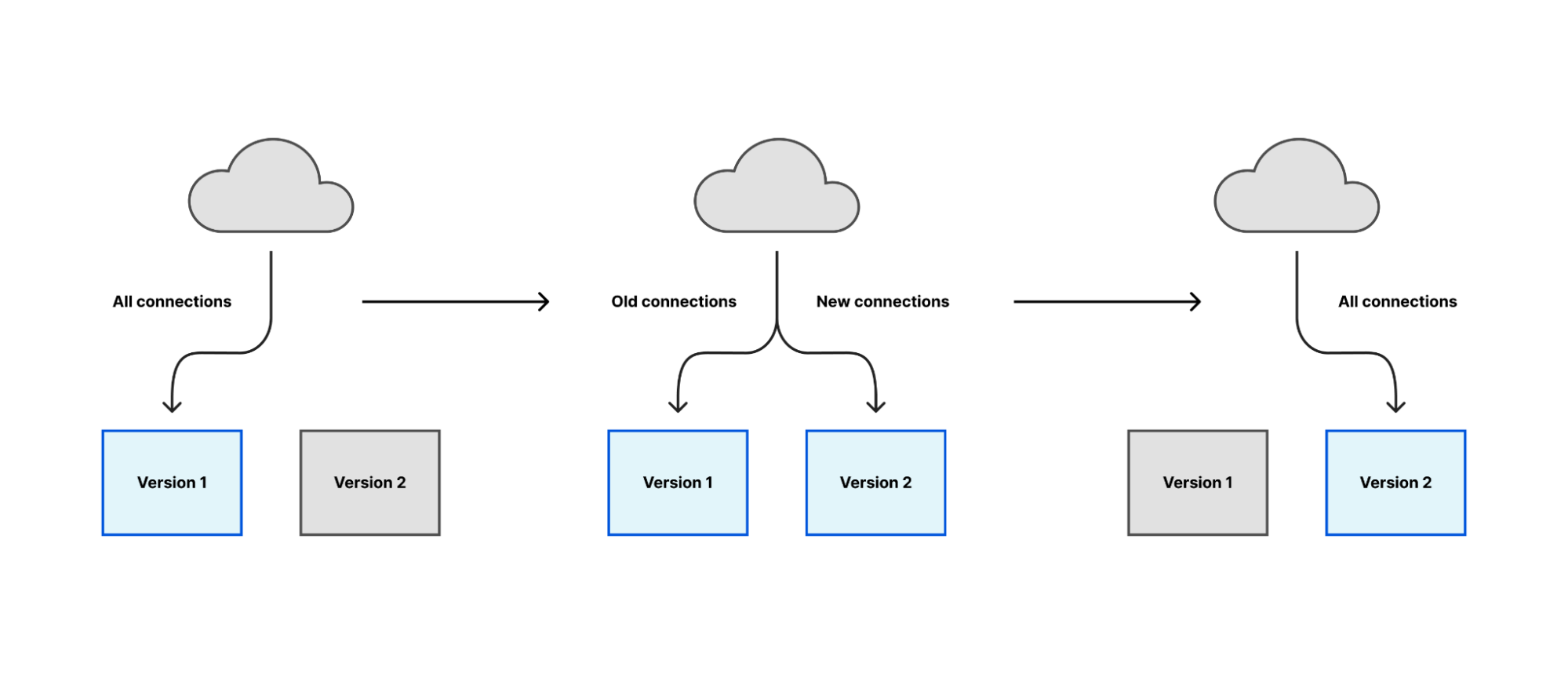

One popular and generally applicable approach is to start a new version of the software, make it responsible for a small number of tasks at first, and then gradually increase its workload until the new version is responsible for everything and the old version responsible for nothing. At that point, you can stop the old version.

Most of Cloudflare’s proxies follow a similar pattern: they receive connections or requests from many clients over the Internet, communicate with other internal services to decide how to serve the request, and fetch content over the Internet if we cannot serve it locally. In general, all of this work happens within the lifetime of a client’s connection. If we aren’t serving any clients, we aren’t doing any work.

The safest time to restart, therefore, is when there is nobody to interrupt. But does such a time really exist? The Internet operates 24 hours a day and many users rely on long-running connections for things like backups, real-time updates or remote shell sessions. Even if you defer restarts to a “quiet” period, the next-best strategy of “interrupt the fewest number of people possible” will fail when you have a critical security fix that needs to be deployed immediately.

Despite this challenge, we have to start somewhere. You rarely arrive at the perfect solution in your first try.

(╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

We have previously blogged about implementing graceful restarts in Cloudflare’s Go projects, using a library called tableflip. This starts a new version of your program and allows the new version to signal to the old version that it started successfully, then lets the old version clear its workload. For a proxy like any Oxy application, that means the old version stops accepting new connections once the new version starts accepting connections, then drives its remaining connections to completion.

This is the simplest case of the migration strategy previously described: the new version immediately takes all new connections, instead of a gradual rollout. But in aggregate across Cloudflare’s server fleet the upgrade process is spread across several hours and the result is as gradual as a deployment orchestrated by Kubernetes or similar.

tableflip also allows your program to bind to sockets, or to reuse the sockets opened by a previous instance. This enables the new instance to accept new connections on the same socket and let the old instance release that responsibility.

Oxy is a Rust project, so we can’t reuse tableflip. We rewrote the spawning/signaling section in Rust, but not the socket code. For that we had an alternative approach.

Socket management with systemd

systemd is a widely used suite of programs for starting and managing all of the system software needed to run a useful Linux system. It is responsible for running software in the correct order – for example ensuring the network is ready before starting a program that needs network access – or running it only if it is needed by another program.

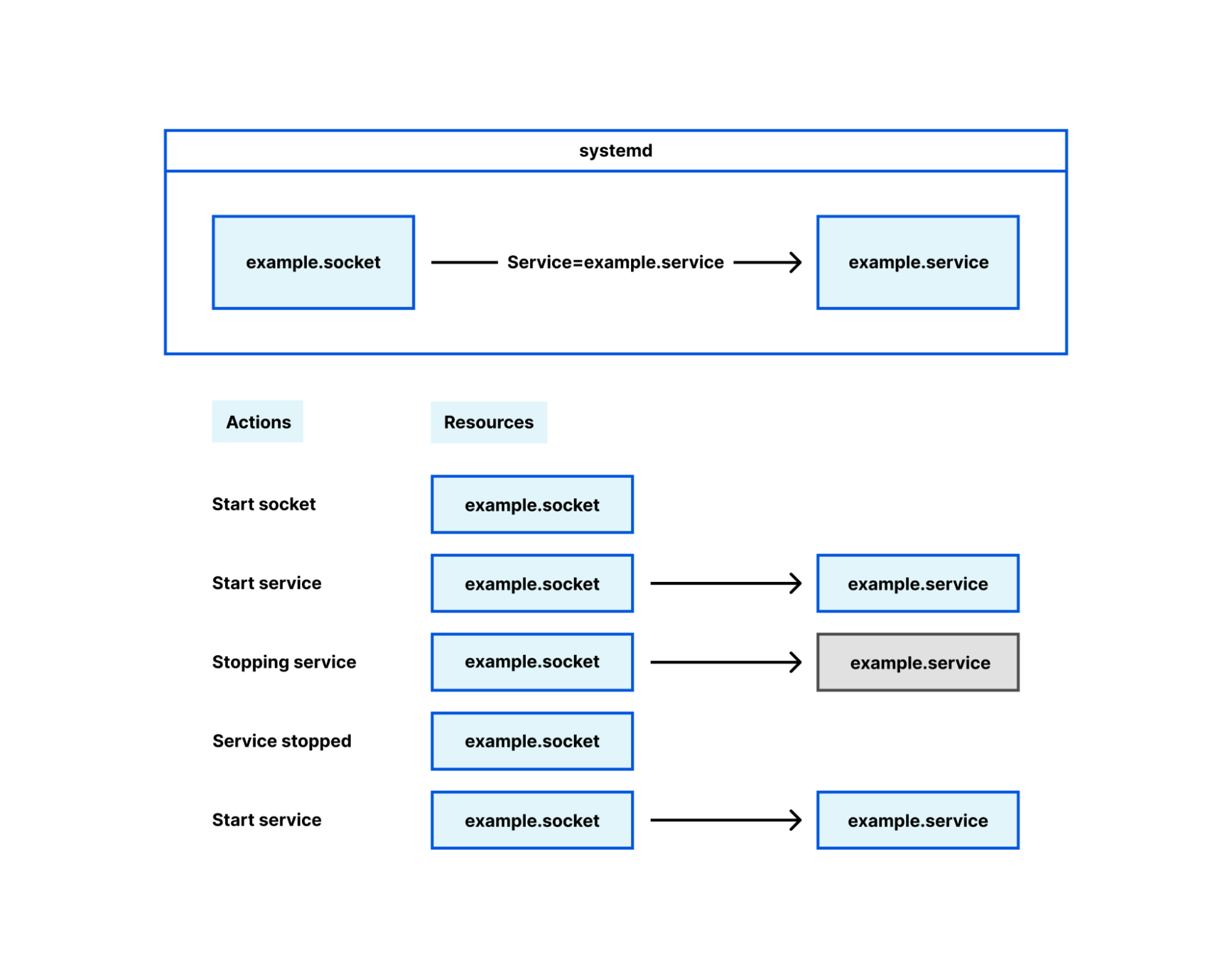

Socket management falls in this latter category, under the term ‘socket activation’. Its intended and original use is interesting but ultimately irrelevant here; for our purposes, systemd is a mere socket manager. Many Cloudflare services configure their sockets using systemd .socket files, and when their service is started the socket is brought into the process with it. This is how we deploy most Oxy-based services, and Oxy has first-class support for sockets opened by systemd.

Using systemd decouples the lifetime of sockets from the lifetime of the Oxy application. When Oxy creates its sockets on startup, if you restart or temporarily stop the Oxy application the sockets are closed. When clients attempt to connect to the proxy during this time, they will get a very unfriendly “connection refused” error. If, however, systemd manages the socket, that socket remains open even while the Oxy application is stopped. Clients can still connect to the socket and those connections will be served as soon as the Oxy application starts up successfully.

Channeling your inner WaitGroup

A useful piece of library code our Go projects use is WaitGroups. These are essential in Go, where goroutines – asynchronously-running code blocks – are pervasive. Waiting for goroutines to complete before continuing another task is a common requirement. Even the example for tableflip uses them, to demonstrate how to wait for tasks to shut down cleanly before quitting your process.

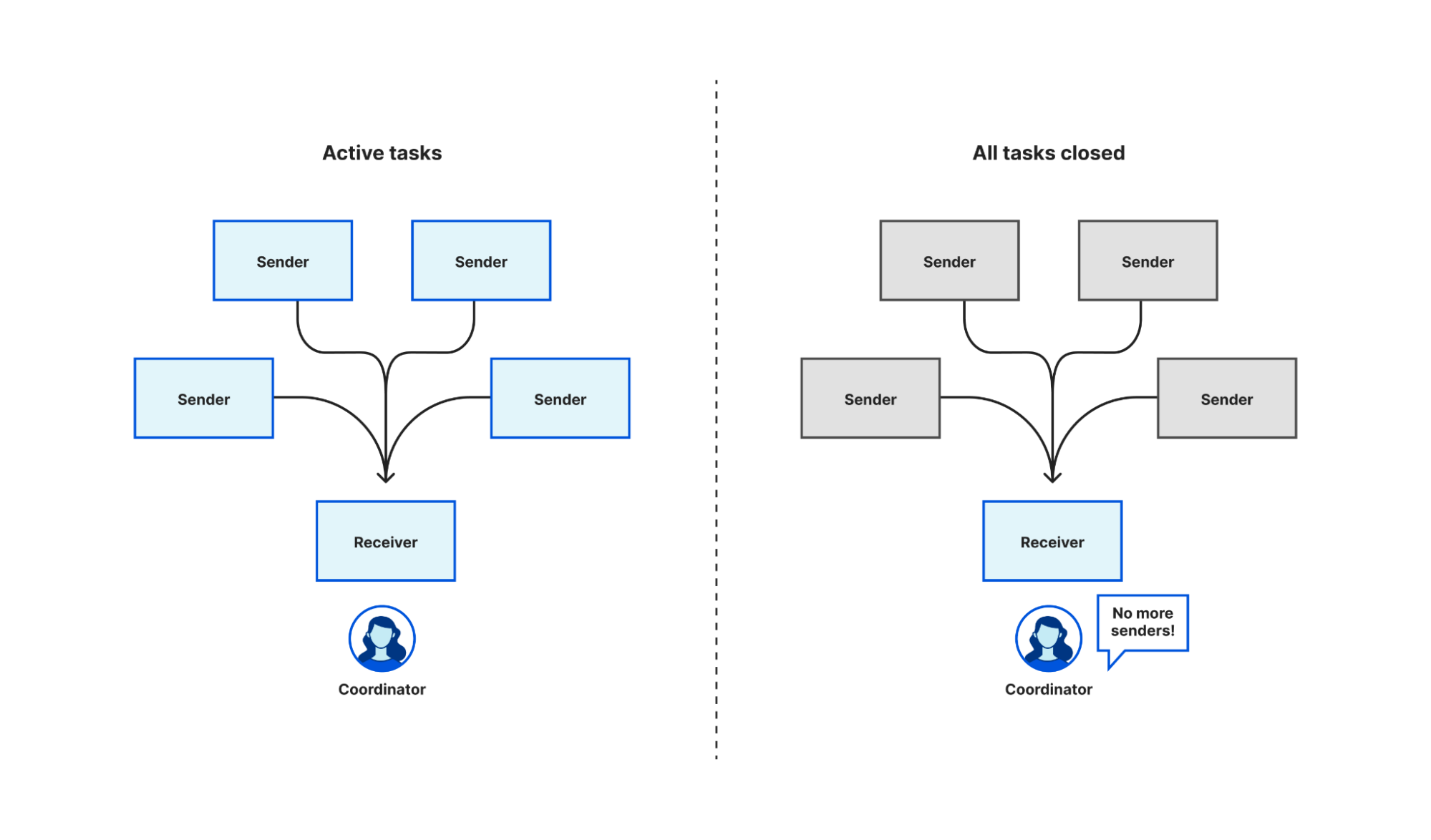

There is not an out-of-the-box equivalent in tokio – the async Rust runtime Oxy uses – or async/await generally, so we had to create one ourselves. Fortunately, most of the building blocks to roll your own exist already. Tokio has multi-producer, single consumer (MPSC) channels, generally used by multiple tasks to push the results of work onto a queue for a single task to process, but we can exploit the fact that it signals to that single receiver when all the sender channels have been closed and no new messages are expected.

To start, we create an MPSC channel. Each task takes a clone of the producer end of the channel, and when that task completes it closes its instance of the producer. When we want to wait for all of the tasks to complete, we await a result on the consumer end of the MPSC channel. When every instance of the producer channel is closed – i.e. all tasks have completed – the consumer receives a notification that all of the channels are closed. Closing the channel when a task completes is an automatic consequence of Rust’s RAII rules. Because the language enforces this rule it is harder to write incorrect code, though in fact we need to write very little code at all.

Getting feedback on failure

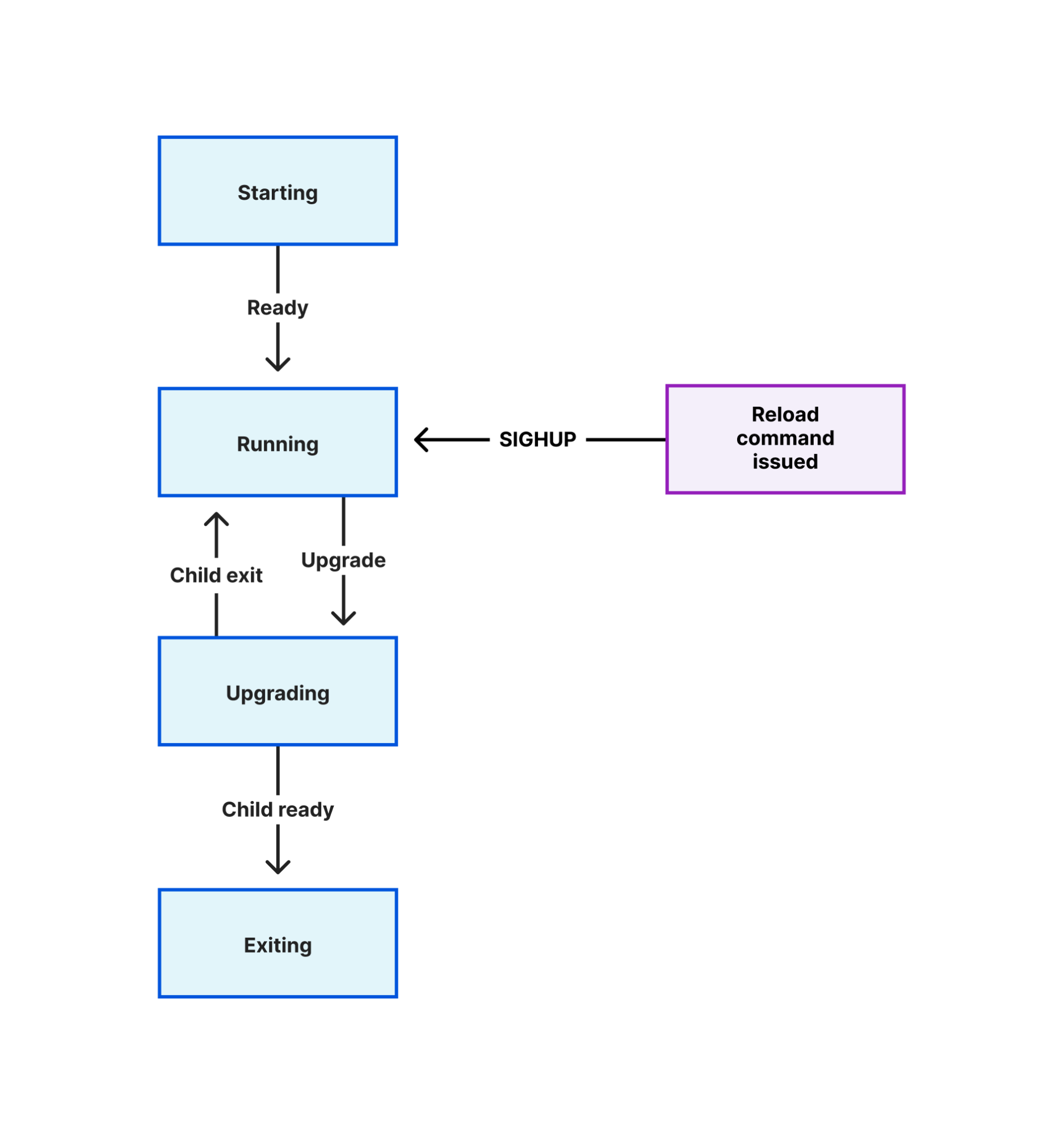

Many programs that implement a graceful reload/restart mechanism use Unix signals to trigger the process to perform an action. Signals are an ancient technique introduced in early versions of Unix to solve a specific problem while creating dozens more. A common pattern is to change a program’s configuration on disk, then send it a signal (often SIGHUP) which the program handles by reloading those configuration files.

The limitations of this technique are obvious as soon as you make a mistake in the configuration, or when an important file referenced in the configuration is deleted. You reload the program and wonder why it isn’t behaving as you expect. If an error is raised, you have to look in the program’s log output to find out.

This problem compounds when you use an automated configuration management tool. It is not useful if that tool makes a configuration change and reports that it successfully reloaded your program, when in fact the program failed to read the change. The only thing that was successful was sending the reload signal!

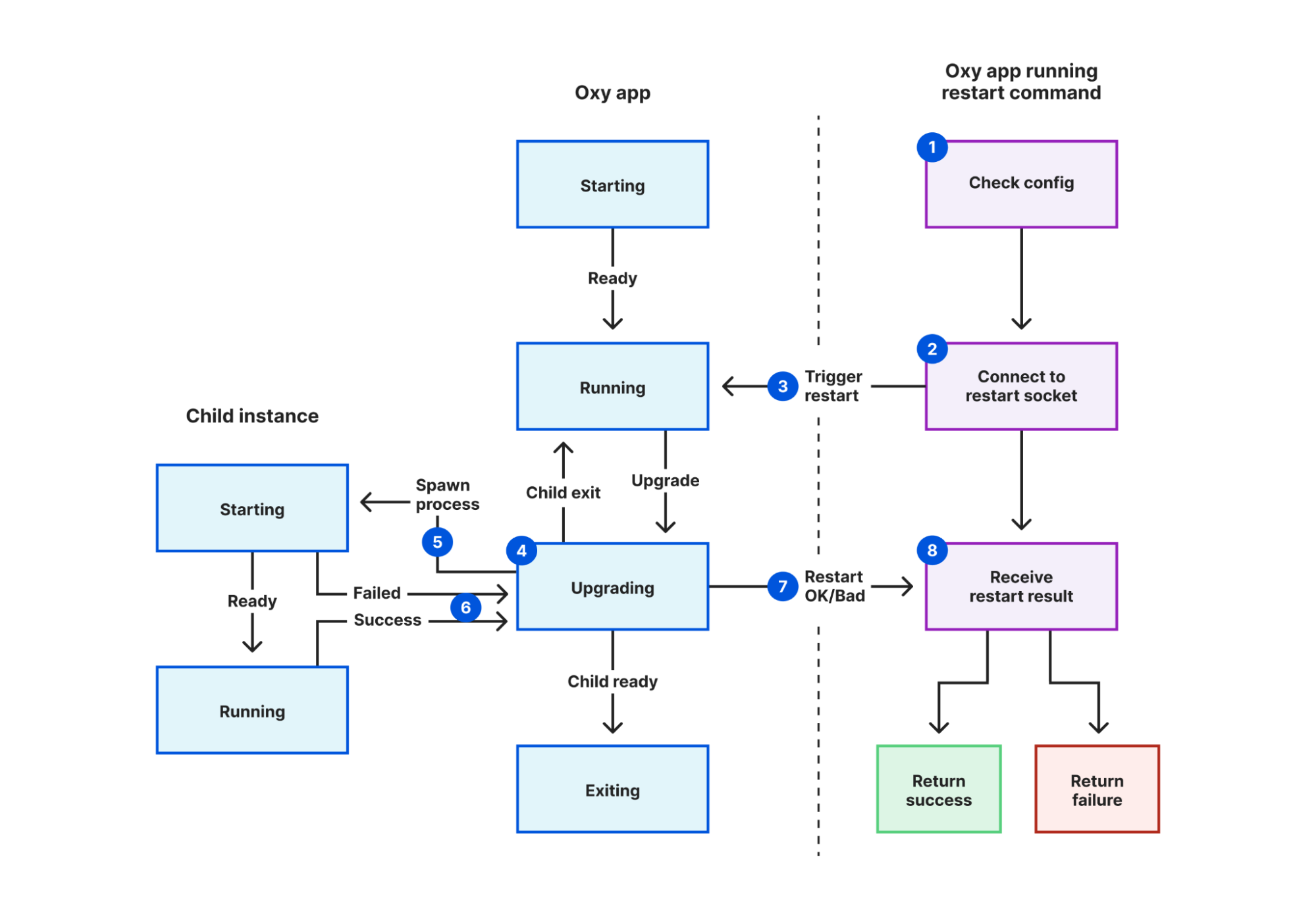

We solved this in Oxy by creating a Unix socket specifically for coordinating restarts, and adding a new mode to Oxy that triggers a restart. In this mode:

- The restarter process validates the configuration file.

- It connects to the restart coordination socket defined in that file.

- It sends a “restart requested” message.

- The current proxy instance receives this message.

- A new instance is started, inheriting a pipe it will use to notify its parent instance.

- The current instance waits for the new instance to report success or fail.

- The current instance sends a “restart response” message back to the restarter process, containing the result.

- The restarter process reports this result back to the user, using exit codes for automated systems to detect failure.

Now when we make a change to any of our Oxy applications, we can be confident that failures are detected using nothing more than our SREs’ existing tooling. This lets us discover failures earlier, narrow down root causes sooner, and avoid our systems getting into an inconsistent state.

This technique is described more generally in a coworker’s blog, using an internal HTTP endpoint instead. Yet HTTP is missing one important property of Unix sockets for the purpose of replacing signals. A user may only send a signal to a process if the process belongs to them – i.e. they started it – or if the user is root. This prevents another user logged into the same machine from you from terminating all of your processes. As Unix sockets are files, they also follow the Unix permission model. Write permissions are required to connect to a socket. Thus we can trivially reproduce the signals security model by making the restart coordination socket user writable only. (Root, as always, bypasses all permission checks.)

Leave no connection behind

We have put a lot of effort into making restarts as graceful as possible, but there are still certain limitations. After restarting, eventually the old process has to terminate, to prevent a build-up of old processes after successive restarts consuming excessive memory and reducing the performance of other running services. There is an upper bound to how long we’ll let the old process run for; when this is reached, any connections remaining are forcibly broken.

The configuration changes that can be applied using graceful restart is limited by the design of systemd. While some configuration like resource limits can now be applied without restarting the service it applies to, others cannot; most significantly, new sockets. This is a problem inherent to the fork-and-inherit model.

For UDP-based protocols like HTTP/3, there is not even a concept of listener socket. The new process may open UDP sockets, but by default incoming packets are balanced between all open unconnected UDP sockets for a given address. How does the old process drain existing sessions without receiving packets intended for the new process and vice versa?

Is there a way to carry existing state to a new process to avoid some of these limitations? This is a hard problem to solve generally, and even in languages designed to support hot code upgrades there is some degree of running old tasks with old versions of code. Yet there are some common useful tasks that can be carried between processes so we can “interrupt the fewest number of people possible”.

Let’s not forget the unplanned outages: segfaults, oomkiller and other crashes. Thankfully rare in Rust code, but not impossible.

You can find the source for our Rust implementation of graceful restarts, named shellflip, in its GitHub repository. However, restarting correctly is just the first step of many needed to achieve our ultimate reliability goals. In a follow-up blog post we’ll talk about some creative solutions to these limitations.