Introducing Zero Round Trip Time Resumption (0-RTT)

Cloudflare’s mission is to help build a faster and more secure Internet. Over the last several years, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has been working on a new version of TLS, the protocol that powers the secure web. Last September, Cloudflare was the first service provider to enable people to use this new version of the protocol, TLS 1.3, improving security and performance for millions of customers.

Today we are introducing another performance-enhancing feature: zero round trip time resumption, abbreviated as 0-RTT. About 60% of the connections we see are from people who are visiting a site for the first time or revisiting after an extended period of time. TLS 1.3 speeds up these connections significantly. The remaining 40% of connections are from visitors who have recently visited a site and are resuming a previous connection. For these resumed connections, standard TLS 1.3 is safer but no faster than any previous version of TLS. 0-RTT changes this. It dramatically speeds up resumed connections, leading to a faster and smoother web experience for web sites that you visit regularly. This speed boost is especially noticeable on mobile networks.

We’re happy to announce that 0-RTT is now enabled by default for all sites on Cloudflare’s free service. For paid customers, it can be enabled in the Crypto app in the Cloudflare dashboard.

This is an experimental feature, and therefore subject to change.

If you’re just looking for a live demo, click here.

The cost of latency

A big component of web performance is transmission latency. Simply put, transmission latency is the amount of time it takes for a message to get from one party to another over a network. Lower latency means snappier web pages and more responsive APIs; when it comes to responsiveness, every millisecond counts.

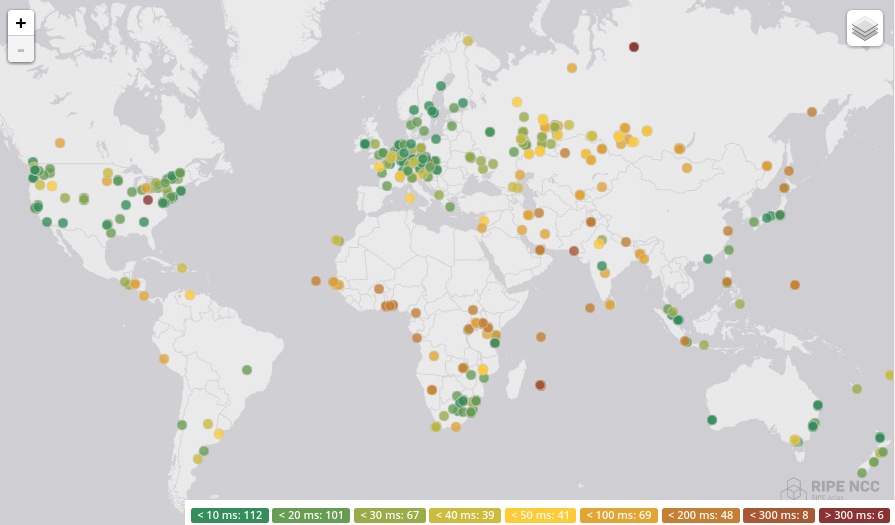

The diagram below comes from a recent latency test of Cloudflare’s network using the RIPE Atlas project. In the experiment, hundreds of probes from around the world sent a single “ping” message to Cloudflare and measured the time it took to get an answer in reply. This time is a good approximation of how long it takes for data to make the round trip from the probe to the server and back, so-called round-trip latency.

Latency is usually measured in milliseconds or thousandths of a second. A thousandth of a second may not seem like a long time, but they can add up quickly. It’s generally accepted that the threshold over which humans no longer perceive something as instantaneous is 100ms. Anything above 100ms will seem fast, but not immediate. For example, Usain Bolt’s reaction time out of the starting blocks in the hundred meter sprint is around 155ms, a good reference point for thinking about latency. Let’s use 155ms, a fast but human perceptible amount of time, as a unit of time measurement. Call 155ms “one Bolt.”

The map above shows that most probes have very low round-trip latency (<20ms) to Cloudflare’s global network. However, for a percentage of probes, the time it takes to reach the nearest Cloudflare data center is much longer, in some cases exceeding 300ms (or two bolts!).

Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic Nick J. Webb

Connections that travel over longer distances have higher latency. Data travel speed is limited by the speed of light. When Cloudflare opens a new datacenter in a new city, latency is reduced for people in the surrounding areas when visiting sites that use Cloudflare. This improvement is often simply because data has a shorter distance to travel.

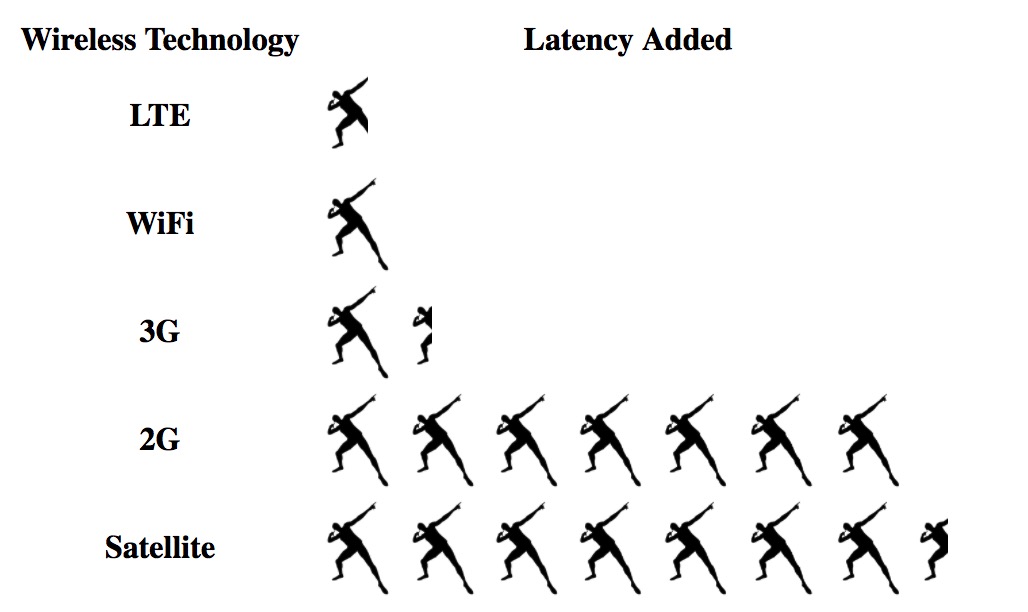

Geographic proximity is not the only contributor to latency. WiFi and cellular networks can add tens or even hundreds of milliseconds to transmission latency. For example, using a 3G cellular network adds around 1.5 bolts to every transmission. Satellite Internet connections are even worse, adding up to 4 bolts to every transmission.

Round-trip latency makes an especially big difference for HTTPS. When making a secure connection to a server, there is an additional set-up phase that can require up to three messages to make the round trip between the client and the server before the first request can even be sent. For a visitor 250ms away, this can result in an excruciating one second (1000ms) delay before a site starts loading. During this time Usain Bolt has run 10 meters and you’re still waiting for a web page. TLS 1.3 and 0-RTT can’t reduce the round trip latency of a transmission, but it can reduce the number of round trips required for setting up an HTTPS connection.

HTTPS round trips

For a browser to download a web page over HTTPS, there is a some setup that goes on behind the scenes. Here are the 4 phases that need to happen the first time your browser tries to access a site.

Phase 1: DNS Lookup

Your browser needs to convert the hostname of the website (say blog.cloudflare.com) into an Internet IP address (like 2400:cb00:2048:1::6813:c166 or 104.19.193.102) before it can connect to it. DNS resolvers operated by your ISP usually cache the IP address for popular domains, and latency to your ISP is fairly low, so this step often takes a negligible amount of time.

Phase 2: TCP Handshake (1 round trip)

The next step is to establish a TCP connection to the server. This phase consists of the client sending a SYN packet to the server, and the server responding with an ACK pack. The details don’t matter as much as the fact that this requires data to be sent from client to server and back. This takes one round trip.

Phase 3: TLS Handshake (2 round trips)

In this phase, the client and server exchange cryptographic key material and set up an encrypted connection. For TLS 1.2 and earlier, this takes two round trips.

Phase 4: HTTP (1 round trip)

Once the TLS connection has been established, your browser can send an encrypted HTTP request using it. This can be a GET request for a specific URL such as https://blog.cloudflare.com/, for example. The server will respond with an HTTP response containing the webpage’s HTML and the browser will start displaying the page.

Assuming DNS is instantaneous, this leaves 4 round trips before the browser can start showing the page. If you’re visiting a site you’ve recently connected to, the TLS handshake phase can be shortened from two round trips to one with TLS session resumption.

This leaves the following minimum wait times:

- New Connection: 4 RTT + DNS

- Resumed Connection: 3 RTT + DNS

How do TLS 1.3 and 0-RTT improve connection times?

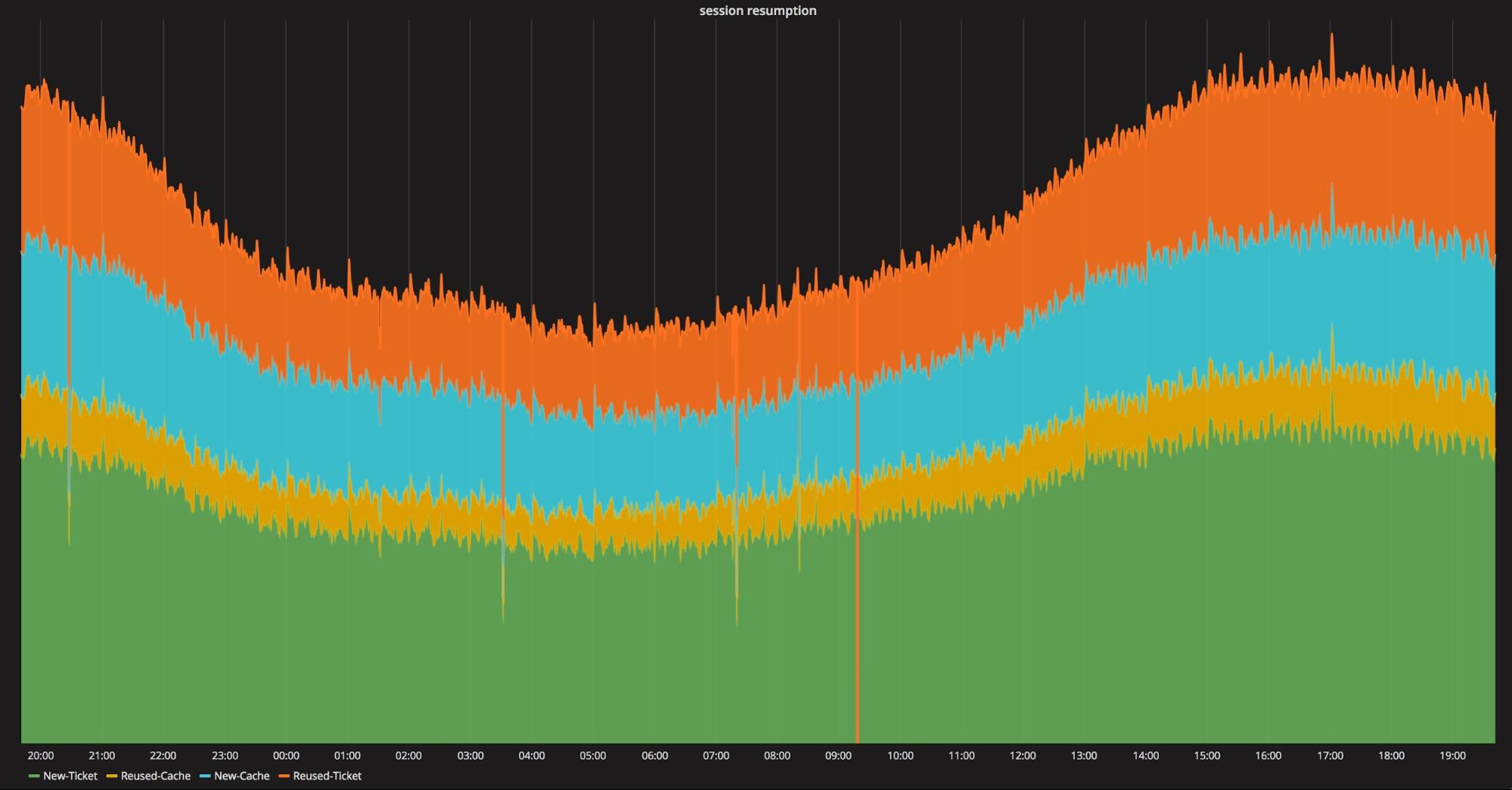

One of the biggest advantages of TLS 1.3 over earlier versions is that it only requires one round trip to set up the connection, resumed or not. This provides a significant speed up for new connections, but none for resumed connections. Our measurements show that around 40% of HTTPS connections are resumptions (either via session IDs or session tickets). With 0-RTT, a round trip can be eliminated for most of that 40%.

TLS connection reuse by time of day.

To summarize the performance differences:

TLS 1.2 (and earlier)

- New Connection: 4 RTT + DNS

- Resumed Connection: 3 RTT + DNS

TLS 1.3

- New Connection: 3 RTT + DNS

- Resumed Connection: 3 RTT + DNS

TLS 1.3 + 0-RTT

- New Connection: 3 RTT + DNS

- Resumed Connection: 2 RTT + DNS

The performance gains are huge.

0-RTT in action

Both Firefox Beta and Chrome Beta have TLS 1.3 enabled by default. The stable versions of Chrome and Firefox also ship with TLS 1.3 support, but it has to be enabled manually for now. The only browsers which supports 0-RTT as of March 2017 are Firefox Nightly and Aurora. To enable it, do the following:

- Enter

about:configin the address bar - Ensure

security.tls.version.maxis 4 (this enables TLS 1.3) - Set

security.tls.enable_0rtt_datato true

This demo loads an image from a server that runs the Cloudflare TLS 1.3 0-RTT proxy. In order to emphasize the latency differences, we used Cloudflare’s new DNS Load Balancer to direct you to a far away server. If the image is loaded over 0-RTT it will be served orange, otherwise black, based on the CF-0RTT-Unique header.

The image is loaded twice: with and without a query string. 0-RTT is disabled transparently when a query string is used to prevent replays.

The connection is pre-warmed, Keep-Alives are off and caching is disabled to simulate the first request of a resumed connection.

0-RTT took: …ms

1-RTT took: …ms

.demo {

text-align: center;

}

.demo a {

font-weight: bold;

text-decoration: none;

color: inherit;

}

.demo p {

margin-top: 1.5em;

}

.images {

max-width: 440px;

margin: 0 auto;

}

.images > div {

width: 200px;

float: left;

margin: 0 10px;

}

.images > div.clear {

float: none;

clear: both;

}

.images img {

width: 100%;

}

var currentStatus = “preparing”;

function demoStatus(s) {

document.querySelector(“.demo .message.”+currentStatus).style.display = “none”;

document.querySelector(“.demo .message.”+s).style.display = “”;

currentStatus = s;

}

function demoLaunch() {

var startTime, startTime0;

var img = document.querySelector(“.demo .images img.nozrtt”);

img.onloadstart = function() {

startTime = new Date().getTime();

};

img.onload = function() {

var loadtime = new Date().getTime() – startTime;

document.querySelector(“.demo .images .time.nozrtt”).innerText = loadtime;

};

var img0 = document.querySelector(“.demo .images img.zrtt”);

img0.onloadstart = function() {

startTime0 = new Date().getTime();

};

img0.onload = function() {

var loadtime = new Date().getTime() – startTime0;

document.querySelector(“.demo .images .time.zrtt”).innerText = loadtime;

window.setTimeout(function() {

img.src = “https://0rtt.tls13.com/img.png?no0rtt”;

}, 2000);

};

img0.src = “https://0rtt.tls13.com/img.png”;

document.querySelector(“.demo .message.ready”).style.display = “none”;

document.querySelector(“.demo .images”).style.display = “”;

};

document.querySelector(“.demo .message.ready a”).onclick = function() {

// var r = new XMLHttpRequest();

// r.addEventListener(“load”, demoLaunch);

// r.open(“GET”, “https://0rtt.tls13.com/img.png?warm”);

// r.send();

demoLaunch();

return false;

};

var r = new XMLHttpRequest();

r.addEventListener(“error”, function() {

demoStatus(“no13”);

document.querySelector(“.demo .fallback”).style.display = “”;

});

r.addEventListener(“loadend”, function() {

var r = new XMLHttpRequest();

r.addEventListener(“error”, function() {

demoStatus(“no13”);

document.querySelector(“.demo .fallback”).style.display = “”;

});

r.addEventListener(“load”, function() {

console.log(this.getResponseHeader(“X-0rtt”));

if (this.getResponseHeader(“X-0rtt”) == “1”) {

demoStatus(“ready”);

} else {

demoStatus(“no0rtt”);

document.querySelector(“.demo .fallback”).style.display = “”;

}

});

window.setTimeout(function() {

r.open(“GET”, “https://0rtt.tls13.com/img.png”);

r.send();

}, 10000);

});

r.open(“GET”, “https://0rtt.tls13.com/img.png”);

r.send();

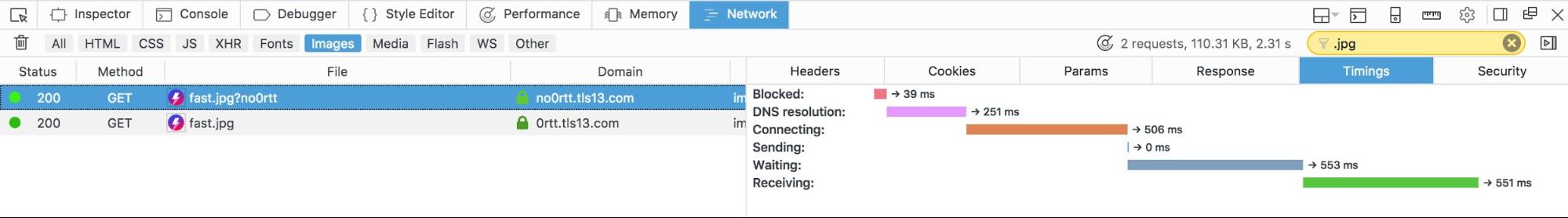

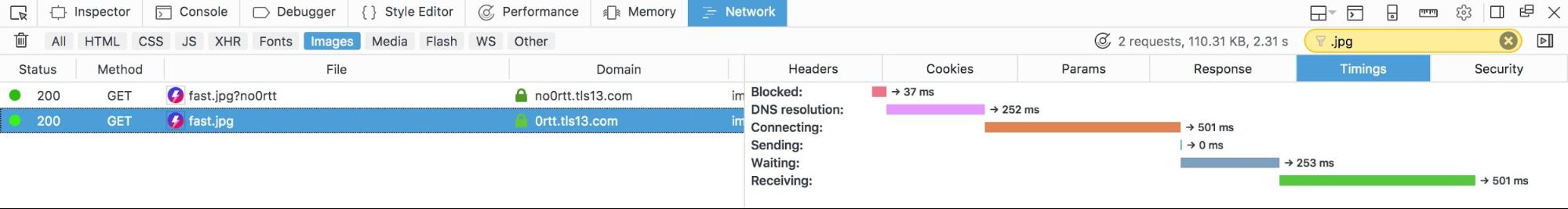

To see what’s going on under the hood, take a look in Firefox’s Developer Tools. We’ve taken a screenshot of a version of this demo as run by a user in San Francisco. In the first screenshot, the image is served with TLS 1.3, in the second with TLS 1.3 and 0-RTT.

In the top image, you can see that the blue “Waiting” bar is around 250ms shorter than it is for the second image. This 250ms represents the time it took for the extra round trip between the browser and the server. If you’re in San Francisco, 0-RTT enables the image to load 1.5 bolts faster than it would have otherwise.

What’s the catch?

0-RTT is cutting edge protocol technology. With it, encrypted HTTPS requests become just as fast as an unencrypted HTTP requests. This sort of breakthrough comes at a cost. This cost is that the security properties that TLS provides to 0-RTT request are slightly weaker than those it provides to regular requests. However, this weakness is manageable, and applications and websites that follow HTTP semantics shouldn’t have anything to worry about. The weakness has to do with replays.

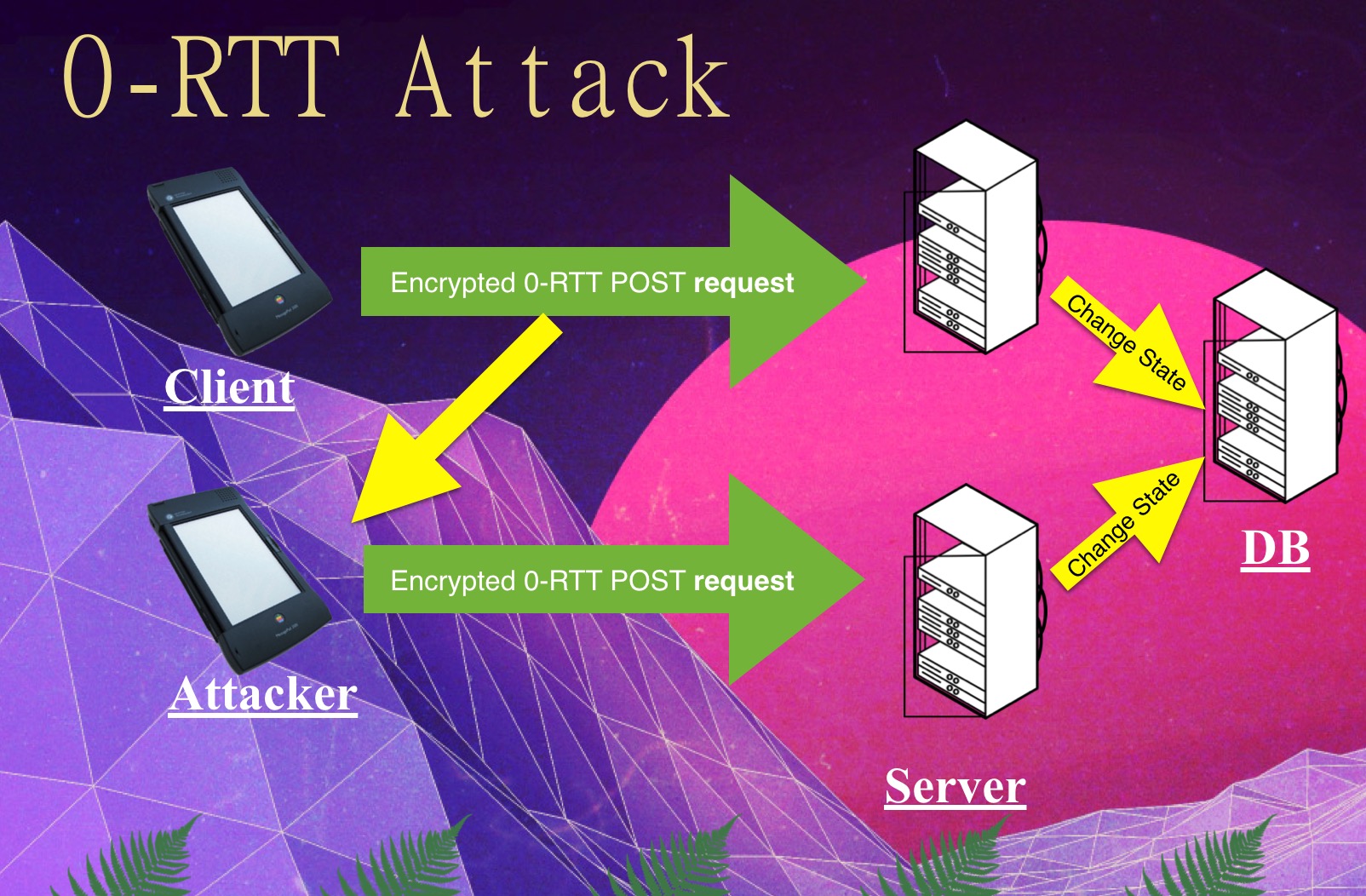

Unlike any other requests sent over TLS, requests sent as part of 0-RTT resumption are vulnerable to what’s called a replay attack. If an attacker has access to your encrypted connection, they can take a copy of the encrypted 0-RTT data (containing your first request) and send it to the server again pretending to be you. This can result in the server seeing repeated requests from you when you only sent one.

This doesn’t sound like a big deal until you consider that HTTP requests are used for more than just downloading web pages. For example, HTTP requests can trigger transfers of money. If someone makes a request to their bank to “pay $1000 to Craig” and that request is replayed, it could cause Craig to be paid multiple times. A good deal if you’re Craig.

Luckily, the example above is somewhat contrived. Applications need to be replay safe to work with modern browsers, whether they support 0-RTT or not. Browsers replay data all the time due to normal network glitches, and researchers from Google have even shown that attackers can trick the browser into to replaying requests in almost any circumstance by triggering a particular type of network error. In order to be resilient against this reality, well-designed web applications that handle sensitive requests use application-layer mechanisms to prevent replayed requests from affecting them.

Although web applications should be replay resilient, that’s not always the reality. To protect these applications from malicious replays, Cloudflare took an extremely conservative approach to choosing which 0-RTT requests would be answered. Specifically, only GET requests with no query parameters are answered over 0-RTT. According to the HTTP specification, GET requests are supposed to be idempotent, meaning that they don’t change the state on the server and shouldn’t be used for things like funds transfer. We also implement a maximum size of 0-RTT requests, and limit how long they can be replayed.

Furthermore, Cloudflare can uniquely identify connection resumption attempts, so we relay this information to the origin by adding an extra header to 0-RTT requests. This header uniquely identifies the request, so if one gets repeated, the origin will know it’s a replay attack.

Here’s what the header looks like:

Cf-0rtt-Unique: 37033bcb6b42d2bcf08af3b8dbae305a

The hexadecimal value is derived from a piece of data called a PSK binder, which is unique per 0-RTT request.

Generally speaking, 0-RTT is safe for most web sites and applications. If your web application does strange things and you’re concerned about its replay safety, consider not using 0-RTT until you can be certain that there are no negative effects.

Conclusion

TLS 1.3 is a big step forward for web performance and security. By combining TLS 1.3 with 0-RTT, the performance gains are even more dramatic. Combine this with HTTP/2 and the encrypted web has never been faster, especially on mobile networks. Cloudflare is happy to be the first to introduce this feature on a wide scale.

No comments yet.