Privacy-preserving measurement and machine learning

In 2023, data-driven approaches to making decisions are the norm. We use data for everything from analyzing x-rays to translating thousands of languages to directing autonomous cars. However, when it comes to building these systems, the conventional approach has been to collect as much data as possible, and worry about privacy as an afterthought.

The problem is, data can be sensitive and used to identify individuals – even when explicit identifiers are removed or noise is added.

Cloudflare Research has been interested in exploring different approaches to this question: is there a truly private way to perform data collection, especially for some of the most sensitive (but incredibly useful!) technology?

Some of the use cases we’re thinking about include: training federated machine learning models for predictive keyboards without collecting every user’s keystrokes; performing a census without storing data about individuals’ responses; providing healthcare authorities with data about COVID-19 exposures without tracking peoples’ locations en masse; figuring out the most common errors browsers are experiencing without reporting which websites are visiting.

It’s with those use cases in mind that we’ve been participating in the Privacy Preserving Measurement working group at the IETF whose goal is to develop systems for collecting and using this data while minimizing the amount of per-user information exposed to the data collector.

So far, the most promising standard in this space is DAP – Distributed Aggregation Protocol – a clever way to use multi-party computation to aggregate data without exposing individual measurements. Early versions of the algorithms used by DAP have been implemented by Google and Apple for exposure notifications.

In this blog post, we’ll do a deep dive into the fundamental concepts behind the DAP protocol and give an example of how we’ve implemented it into Daphne, our open source aggregator server. We hope this will inspire others to collaborate with us and get involved in this space!

The principles behind DAP, an open standard for privacy preserving measurement

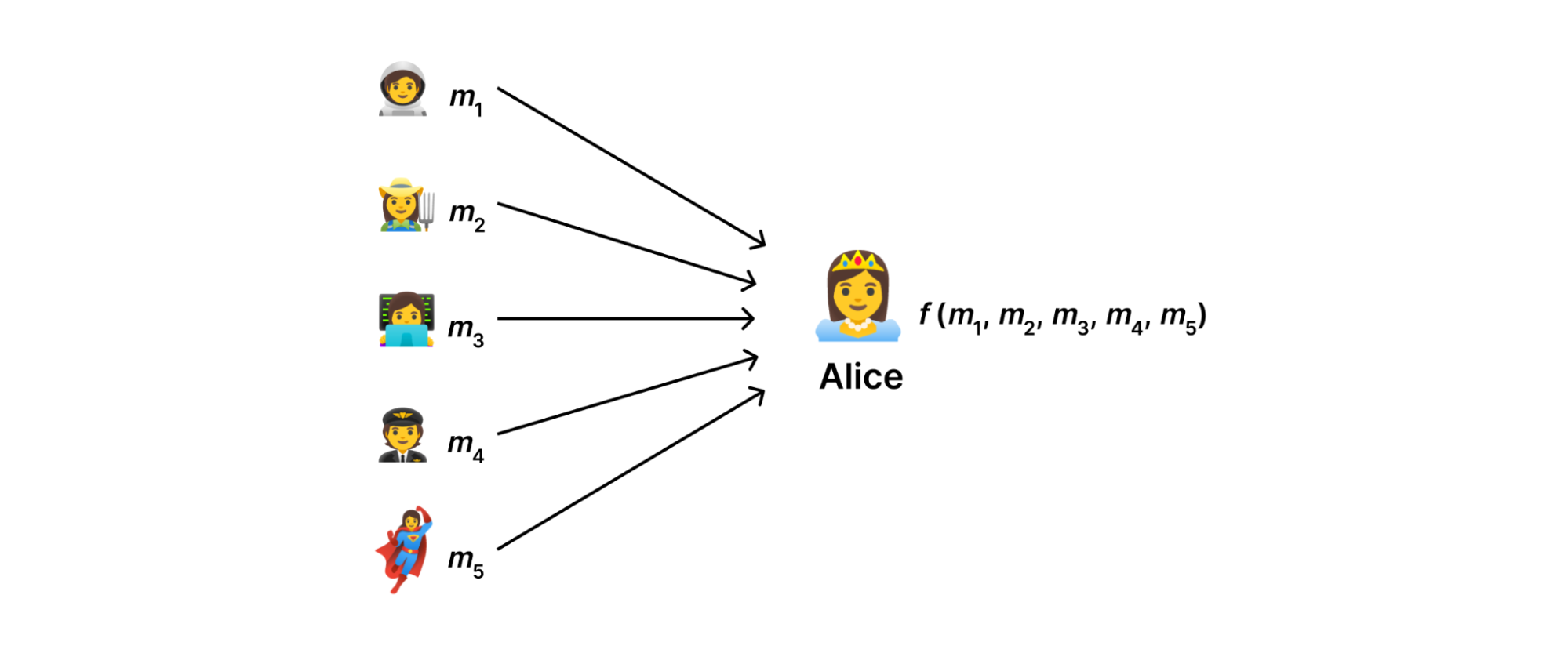

At a high level, using the DAP protocol forces us to think in terms of data minimization: collect only the data that we use and nothing more. Abstractly, our goal is to devise a system with which a data collector can compute some function ( f(m_{1},…,m_{N}) ) of measurements ( m_{1},…,m_{N} ) uploaded by users without observing the measurements in the clear.

This may at first seem like an impossible task: to compute on data without knowing the data we're computing on. Nevertheless, —and, as is often the case in cryptography— once we've properly constrained the problem, solutions begin to emerge.

In an ideal world (see above), there would be some server somewhere on the Internet that we could trust to consume measurements, aggregate them, and send the result to the data collector without ever disclosing anything else. However, in reality there's no reason for users to trust such a server more than the data collector; Indeed, both are subject to the usual assortment of attacks that can lead to a data breach.

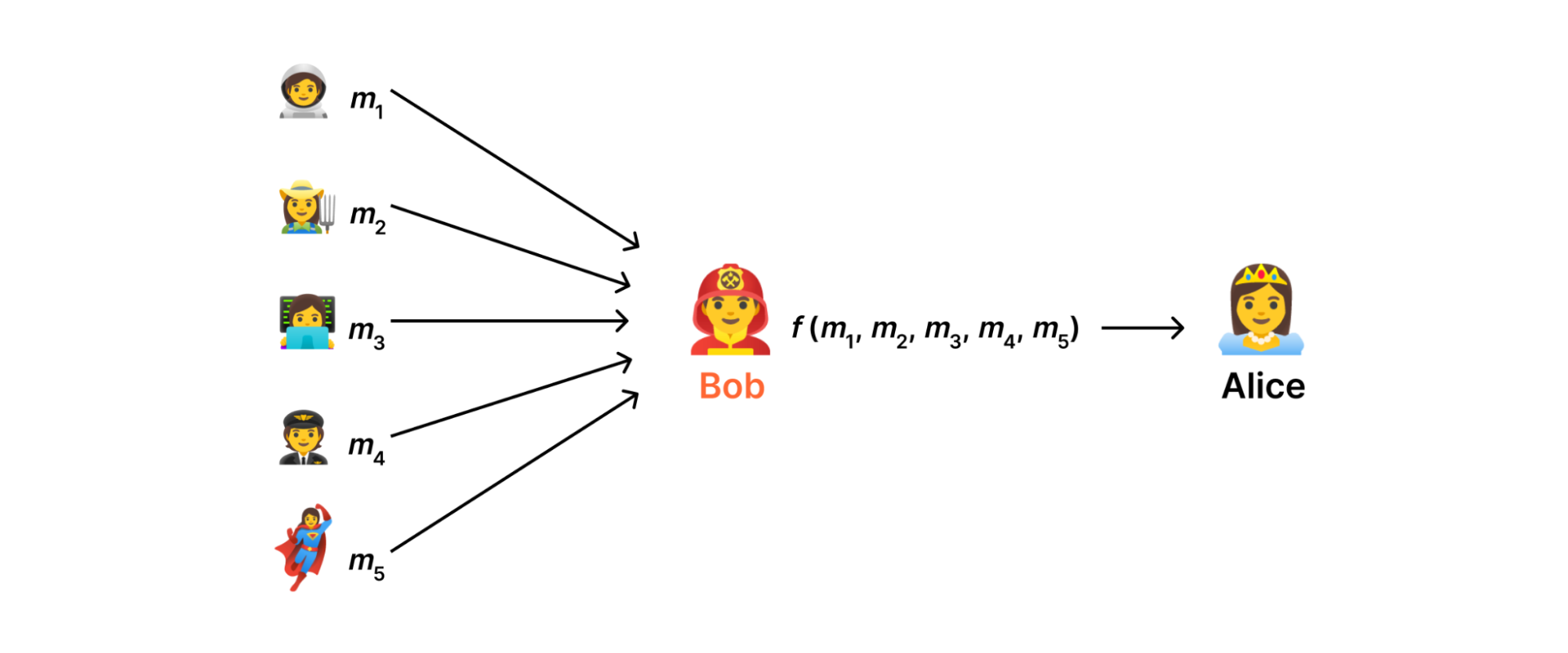

Instead, what we do in DAP is distribute the computation across the servers such that no single server has a complete measurement. The key idea that makes this possible is secret sharing.

Computing on secret shared data

To set things up, let's make the problem a little more concrete. Suppose each measurement ( m_{i} ) is a number and our goal is to compute the sum of the measurements. That is, ( f(m_{1},…,m_{N}) = m_{1} + cdots + m_{N} ). Our goal is to use secret sharing to allow two servers, which we'll call aggregators, to jointly compute this sum.

To understand secret sharing, we're going to need a tiny bit of math—modular arithmetic. The expression ( X + 1 (textrm{mod}) textit{q} ) means “add ( X ) and ( Y ), then divide the sum by ( q ) and return the remainder”. For now the modulus ( q ) can be any large number, as long as it's larger than any sum we'd ever want to compute (( 2 ^{64} ), say). In the remainder of this section, we'll omit ( q ) and simply write ( X + Y ) for addition modulo ( q ).

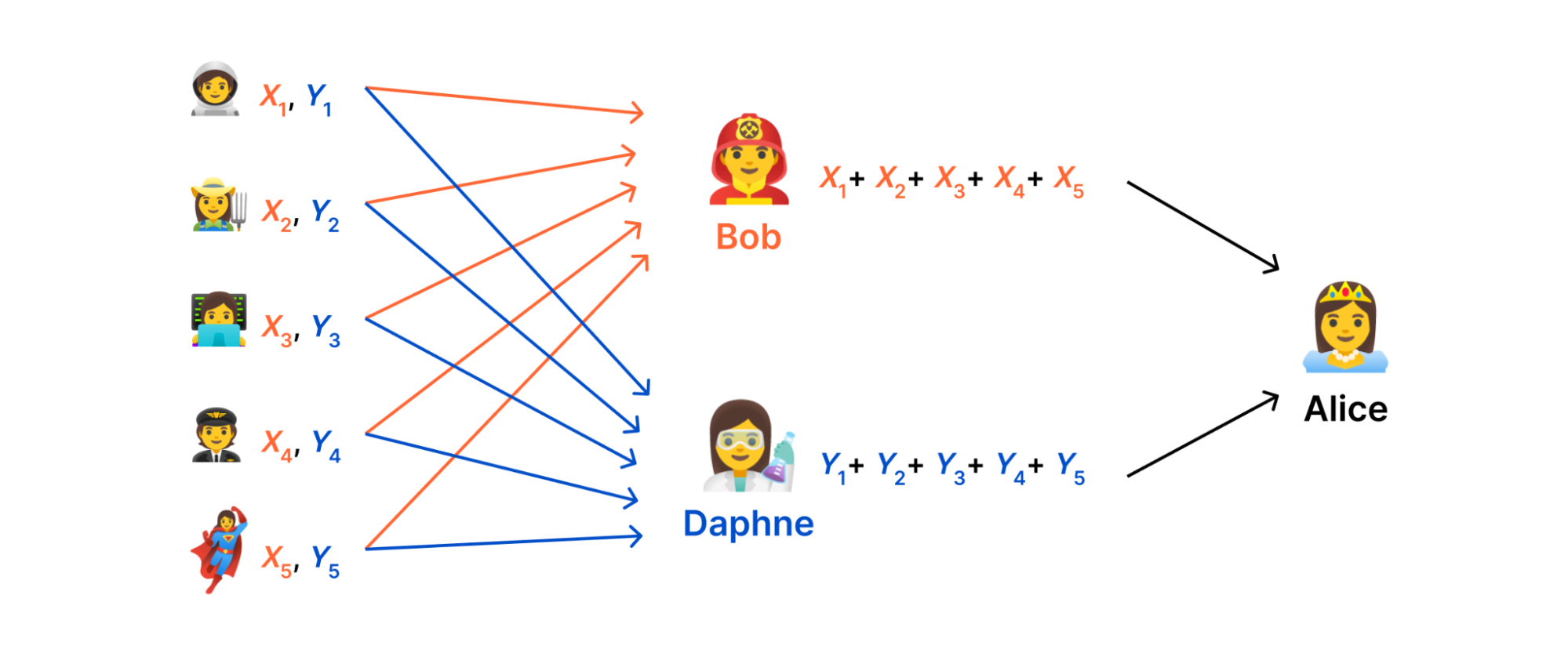

The goal of secret sharing is to shard a measurement (i.e., a “secret”) into two “shares” such that (i) the measurement can be recovered by combining the shares together and (ii) neither share leaks any information about the measurement. To secret share each ( m_{i} ), we choose a random number ( R_{i} in lbrace 0,…,q – 1rbrace ), set the first share to be (X_{i} = m_{i} – R_{i} ) and set the other share to be ( Y_{i} = R_{i} ). To recover the measurement, we simply add the shares together. This works because ( X_{i} + Y_{i} = (m_{i} – R_{i}) + R_{i} = m_{i} ). Moreover, each share is indistinguishable from a random number: For example, ( 1337 ) might be secret-shared into ( 11419752798245067454 ) and ( 7026991275464485499 ) (modulo ( q = 2^{64} )).

With this scheme we can devise a simple protocol for securely computing the sum:

- Each client shards its measurement ( m_{i} ) into ( X_{i} ) and ( Y_{i} ) and sends one share to each server.

- The first aggregator computes ( X = X_{1} + cdots + X_{N} ) and reveals ( X ) to the data collector. The second aggregator computes ( Y = Y_{1} + cdots + Y_{N} ) and reveals ( Y ) to the data collector.

- The data collector unshards the result as ( r = X + Y ).

This works because the secret shares are additive, and the order in which we add things up is irrelevant to the function we're computing:

( r = m_{1} + cdots + m_{N} ) // by definition

( r = (m_{1} – R_{1}) + R_{1} + cdots (m_{N} – R_{N}) + R_{N} ) // apply sharding

( r = (m_{1} – R_{1}) + cdots + (m_{N} – R_{N}) + R_{1} + cdots R_{N} ) // rearrange the sum

( r = X + Y ) // apply aggregation

Rich data types

This basic template for secure aggregation was described in a paper from Henry Corrigan-Gibbs and Dan Boneh called “Prio: Private, Robust, and Scalable Computation of Aggregate Statistics” (NSDI 2017). This paper is a critical milestone in DAP's history, as it showed that a wide variety of aggregation tasks (not just sums) can be solved within one, simple protocol framework, Prio. With DAP, our goal in large part is to bring this framework to life.

All Prio tasks are instances of the same template. Measurements are encoded in a form that allows the aggregation function to be expressed as the sum of (shares of) the encoded measurements. For example:

- To get arithmetic mean, we just divide the sum by the number of measurements.

- Variance and standard deviation can be expressed as a linear function of the sum and the sum of squares (i.e., ( m_{i}, m_{i}^{2} ) for each ( i )).

- Quantiles (e.g., median) can be estimated reasonably well by mapping the measurements into buckets and aggregating the histogram.

- Linear regression (i.e., finding a line of best fit through a set of data points) is a bit more complicated, but can also be expressed in the Prio framework.

This degree of flexibility is essential for wide-spread adoption because it allows us to get the most value we can out of a relatively small amount of software. However, there are a couple problems we still need to overcome, both of which entail the need for some form of interaction.

Input validation

The first problem is input validation. Software engineers, especially those of us who operate web services, know in our bones that validating inputs we get from clients is of paramount importance. (Never, ever stick a raw input you got from a client into an SQL query!) But if the inputs are secret shared, then there is no way for an aggregator to discern even a single bit of the measurement, let alone check that it has an expected value. (A secret share of a valid measurement and a number sampled randomly from ( lbrace 0,…,q – 1 rbrace ) look identical.) At least, not on its own.

The solution adopted by Prio (and the standard, with some improvements), is a special kind of zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) system designed to operate on secret shared data. The goal is for a prover to convince a verifier that a statement about some data it has committed to is true (e.g., the user has a valid hardware key), without revealing the data itself (e.g. which hardware key is in-use).

Our setting is exactly the same, except that we're working on secret-shared data rather than committed data. Along with the measurement shares, the client sends shares of a validity proof; then during aggregation, the aggregators interact with one another in order to check and verify the proof. (One round-trip over the network is required.)

A happy consequence of working with secret shared data is that proof generation and verification are much faster than for committed (or encrypted) data. This is mainly because we avoid the use of public-key cryptography (i.e., elliptic curves) and are less constrained in how we choose cryptographic parameters. (We require the modulus ( q ) to be a prime number with a particular structure, but such primes are not hard to find.)

Non-linear aggregation

There are a variety of aggregation tasks for which Prio is not well-suited, in particular those that are non-linear. One such task is to find the “heavy hitters” among the set of measurements. The heavy hitters are the subset of the measurements that occur most frequently, say at least ( t ) times for some threshold ( t ). For example, the measurements might be the URLs visited on a given day by users of a web browser; the heavy hitters would be the set of URLs that were visited by at least ( t ) users.

This computation can be expressed as a simple program:

def heavy_hitters(measurements: list[bytes], t: int) -> set[bytes]:

hh = defaultdict(lambda: 0)

for measurement in measurements:

hh[measurement] += 1

return set(map(lambda x: x[0], filter(lambda x: x[1] >= t, hh.items())))

However, it cannot be expressed as a linear function, at least not efficiently (with sub-exponential space). This would be required to perform this computation on secret-shared measurements.

In order to enable non-linear computation on secret shared data, it is necessary to introduce some form of interaction. There are a few possibilities. For the heavy hitters problem in particular, Henry Corrigan-Gibbs and others devised a protocol called Poplar (IEEE Security & Privacy 2021) in which several rounds of aggregation and unsharding are performed, where in each round, information provided by the collector is used to “query” the measurements to obtain a refined aggregate result.

Helping to build a world of multi-party computation

Protocols like Prio or Poplar that enable computation over secret shared data fit into a rich tradition in cryptography known as multi-party computation (MPC). MPC is at once an active research area in theoretical computer science and a class of protocols that are beginning to see real-world use—in our case, to minimize the amount of privacy-sensitive information we collect in order to keep the Internet moving.

The PPM working group at IETF represents a significant effort, by Cloudflare and others, to standardize MPC techniques for privacy preserving measurement. This work has three main prongs:

- To identify the types of problems that need to be solved.

- To provide cryptography researchers from academia, industry, and the public sector with “templates” for solutions that we know how to deploy. One such template is called a “Verifiable Distributed Aggregation Function (VDAF)”, which specifies a kind of “API boundary” between protocols like Prio and Poplar and the systems that are built around them. Cloudflare Research is leading development of the standard, contributing to implementations, and providing security analysis.

- To provide a deployment roadmap for emerging protocols. DAP is one such roadmap: it specifies execution of a generic VDAF over HTTPS and attends to the various operational considerations that arise as deployments progress. As well as contributing to the standard itself, Cloudflare has developed its own implementation designed for our own infrastructure (see below).

The IETF is working on its first set of drafts (DAP/VDAF). These drafts are mature enough to deploy, and a number of deployments are scaling up as we speak. Our hope is that we have initiated positive feedback between theorists and practitioners: as new cryptographic techniques emerge, more practitioners will begin to work with them, which will lead to identifying new problems to solve, leading to new techniques, and so on.

Daphne: Cloudflare’s implementation of a DAP Aggregation Server

Our emerging technology group has been working on Daphne, our Rust-based implementation of a DAP aggregator server. This is only half of a deployment – DAP architecture requires two aggregator servers to interoperate, both operated by different parties. Our current version only implements the DAP Helper role; the other role is the DAP Leader. Plans are in the works to implement the Leader as well, which will open us up to deploy Daphne for more use cases.

We made two big decisions in our implementation here: using Rust and using Workers. Rust has been skyrocketing in popularity in the past few years due to its performance and memory management – a favorite of cryptographers for similar reasons. Workers is Cloudflare’s serverless execution environment that allows developers to easily deploy applications globally across our network – making it a favorite tool to prototype with at Cloudflare. This allows for easy integration with our Workers-based storage solutions like: Durable Objects, which we’re using for storing various data artifacts as required by the DAP protocol; and KV, which we’re using for managing aggregation task configuration. We’ve learned a lot from our interop tests and deployment, which has helped improve our own Workers products and which we have also fed back into the PPM working group to help improve the DAP standard.

If you’re interested in learning more about Daphne or collaborating with us in this space, you can fill out this form. If you’d like to get involved in the DAP standard, you can check out the working group.