Reflections on reflection (attacks)

Recently Akamai published an article about CLDAP reflection attacks. This got us thinking. We saw attacks from Conectionless LDAP servers back in November 2016 but totally ignored them because our systems were automatically dropping the attack traffic without any impact.

We decided to take a second look through our logs and share some statistics about reflection attacks we see regularly. In this blog post, I’ll describe popular reflection attacks, explain how to defend against them and why Cloudflare and our customers are immune to most of them.

A recipe for reflection

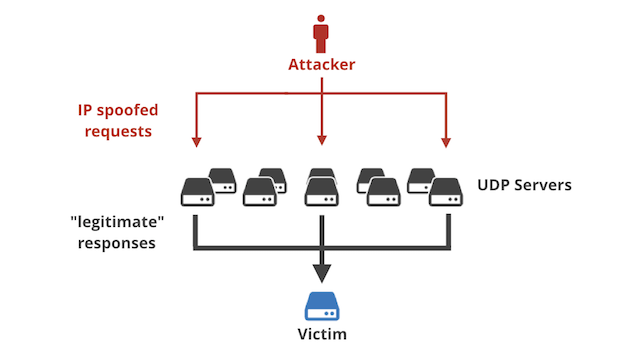

Let’s start with a brief reminder on how reflection attacks (often called “amplification attacks”) work.

To bake a reflection attack, the villain needs four ingredients:

- A server capable of performing IP address spoofing.

- A protocol vulnerable to reflection/amplification. Any badly designed UDP-based request-response protocol will do.

- A list of “reflectors”: servers that support the vulnerable protocol.

- A victim IP address.

The general idea:

- The villain sends fake UDP requests.

- The source IP address in these packets is spoofed: the attacker sticks the victim’s IP address in the source IP address field, not their own IP address as they normally would.

- Each packet is destined to a random reflector server.

- The spoofed packets traverse the Internet and eventually are delivered to the reflector server.

- The reflector server receives the fake packet. It looks at it carefully and thinks: “Oh, what a nice request from the victim! I must be polite and respond!”. It sends the response in good faith.

- The response, though, is directed to the victim.

The victim will end up receiving a large volume of response packets it never had requested. With a large enough attack the victim may end up with congested network and an interrupt storm.

The responses delivered to victim might be larger than the spoofed requests (hence amplification). A carefully mounted attack may amplify the villain’s traffic. In the past we’ve documented a 300Gbps attack generated with an estimated 27Gbps of spoofing capacity.

Popular reflections

During the last six months our DDoS mitigation system “Gatebot” detected 6,329 simple reflection attacks (that’s one every 40 minutes). Here is the list by popularity of different attack vectors. An attack is defined as a large flood of packets identified by a tuple: (Protocol, Source Port, Target IP). Basically – a flood of packets with the same source port to a single target. This notation is pretty accurate – during normal Cloudflare operation, incoming packets rarely share a source port number!

Count Proto Src port

3774 udp 123 NTP

1692 udp 1900 SSDP

438 udp 0 IP fragmentation

253 udp 53 DNS

42 udp 27015 SRCDS

20 udp 19 Chargen

19 udp 20800 Call Of Duty

16 udp 161 SNMP

12 udp 389 CLDAP

11 udp 111 Sunrpc

10 udp 137 Netbios

6 tcp 80 HTTP

5 udp 27005 SRCDS

2 udp 520 RIP

Source port 123/udp NTP

By far the most popular reflection attack vector remains NTP. We have blogged about NTP in the past:

- Understanding and mitigating NTP-based DDoS attacks

- Technical Details Behind a 400Gbps NTP Amplification DDoS Attack

- Good News: Vulnerable NTP Servers Closing Down

Over the last six months we’ve seen 3,374 unique NTP amplification attacks. Most of them were short. The average attack duration was 11 minutes, with the longest lasting 22 hours (1,300 minutes). Here’s a histogram showing the distribution of NTP attack duration:

Minutes min:1.00 avg:10.51 max:1297.00 dev:35.02 count:3774

Minutes:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

0 | 2

1 | * 53

2 | ************************* 942

4 |************************************************** 1848

8 | *************** 580

16 | ***** 221

32 | * 72

64 | 35

128 | 11

256 | 7

512 | 2

1024 | 1

Most of the attacks used a small number of reflectors – we’ve recorded an average of 1.5k unique IPs per attack. The largest attack used an estimated 12.3k reflector servers.

Unique IPs min:5.00 avg:1552.84 max:12338.00 dev:1416.03 count:3774

Unique IPs:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

16 | 0

32 | 1

64 | 8

128 | ***** 111

256 | ************************* 553

512 | ************************************************* 1084

1024 |************************************************** 1093

2048 | ******************************* 685

4096 | ********** 220

8192 | 13

The peak attack bandwidth was on average 5.76Gbps and max of 64Gbps:

Peak bandwidth in Gbps min:0.06 avg:5.76 max:64.41 dev:6.39 count:3774

Peak bandwidth in Gbps:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

0 | ****** 187

1 | ********************* 603

2 |************************************************** 1388

4 | ***************************** 818

8 | ****************** 526

16 | ******* 212

32 | * 39

64 | 1

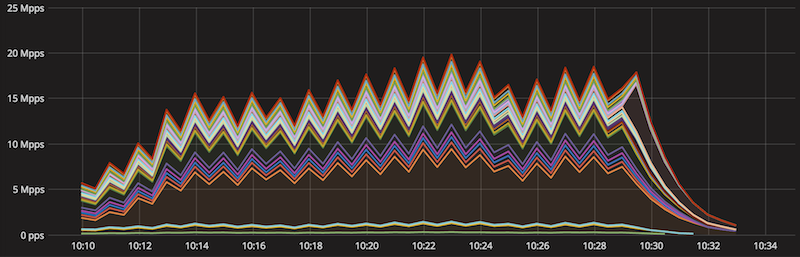

This stacked chart shows the geographical distribution of the largest NTP attack we’ve seen in the last six months. You can see the packets per second number directed to each datacenter. One our datacenters (San Jose to be precise) received about a third of the total attack volume, while the remaining packets were distributed roughly evenly across other datacenters.

The attack lasted 20 minutes, used 527 reflector NTP servers and generated about 20Mpps / 64Gbps at peak.

Dividing these numbers we can estimate that a single packet in that attack had on average size of 400 bytes. In fact, in NTP attacks the great majority of packets have a length of precisely 468 bytes (less often 516). Here’s a snippet from tcpdump:

$ tcpdump -n -r 3164b6fac836774c.pcap -v -c 5 -K

11:38:06.075262 IP -(tos 0x20, ttl 60, id 0, offset 0, proto UDP (17), length 468)

216.152.174.70.123 > x.x.x.x.47787: [|ntp]

11:38:06.077141 IP -(tos 0x0, ttl 56, id 0, offset 0, proto UDP (17), length 468)

190.151.163.1.123 > x.x.x.x.44540: [|ntp]

11:38:06.082631 IP -(tos 0xc0, ttl 60, id 0, offset 0, proto UDP (17), length 468)

69.57.241.60.123 > x.x.x.x.47787: [|ntp]

11:38:06.095971 IP -(tos 0x0, ttl 60, id 0, offset 0, proto UDP (17), length 468)

126.219.94.77.123 > x.x.x.x.21784: [|ntp]

11:38:06.113935 IP -(tos 0x0, ttl 59, id 0, offset 0, proto UDP (17), length 516)

69.57.241.60.123 > x.x.x.x.9285: [|ntp]

Source port 1900/udp SSDP

The second most popular reflection attack was SSDP, with a count of 1,692 unique events. These attacks were using much larger fleets of reflector servers. On average we’ve seen around 100k reflectors used in each attack, with the largest attack using 1.23M reflector IPs. Here’s the histogram of number of unique IPs used in SSDP attacks:

Unique IPs min:15.00 avg:98272.02 max:1234617.00 dev:162699.90 count:1691

Unique IPs:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

256 | 0

512 | 4

1024 | **************** 98

2048 | ************************ 152

4096 | ***************************** 178

8192 | ************************* 158

16384 | **************************** 176

32768 | *************************************** 243

65536 |************************************************** 306

131072 | ************************************ 225

262144 | *************** 95

524288 | ******* 47

1048576 | * 7

The attacks were also longer, with 24 minutes average duration:

$ cat 1900-minutes| ~/bin/mmhistogram -t "Minutes"

Minutes min:2.00 avg:23.69 max:1139.00 dev:57.65 count:1692

Minutes:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

0 | 0

1 | 10

2 | ***************** 188

4 | ******************************** 354

8 |************************************************** 544

16 | ******************************* 342

32 | *************** 168

64 | **** 48

128 | * 19

256 | * 16

512 | 1

1024 | 2

Interestingly the bandwidth doesn’t follow a normal distribution. The average SSDP attack was 12Gbps and the largest just shy of 80Gbps:

$ cat 1900-Gbps| ~/bin/mmhistogram -t "Bandwidth in Gbps"

Bandwidth in Gbps min:0.41 avg:11.95 max:78.03 dev:13.32 count:1692

Bandwidth in Gbps:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

0 | ******************************* 331

1 | ********************* 232

2 | ********************** 235

4 | *************** 165

8 | ****** 65

16 |************************************************** 533

32 | *********** 118

64 | * 13

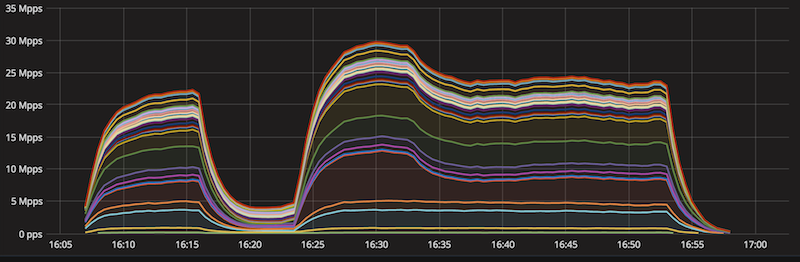

Let’s take a closer look at the largest (80Gbps) attack we’ve recorded. Here’s a stacked chart showing packets per second going to each datacenter. This attack was using 940k reflector IPs, generated 30Mpps. The datacenters receiving the largest proportion of the traffic were San Jose, Los Angeles and Moscow.

The average packet size was 300 bytes. Here’s how the attack looked on the wire:

$ tcpdump -n -r 4ca985a2211f8c88.pcap -K -c 7

10:24:34.030339 IP - 219.121.108.27.1900 > x.x.x.x.25255: UDP, length 301

10:24:34.406943 IP - 208.102.119.37.1900 > x.x.x.x.37081: UDP, length 331

10:24:34.454707 IP - 82.190.96.126.1900 > x.x.x.x.25255: UDP, length 299

10:24:34.460455 IP - 77.49.122.27.1900 > x.x.x.x.25255: UDP, length 289

10:24:34.491559 IP - 212.171.247.139.1900 > x.x.x.x.25255: UDP, length 323

10:24:34.494385 IP - 111.1.86.109.1900 > x.x.x.x.37081: UDP, length 320

10:24:34.495474 IP - 112.2.47.110.1900 > x.x.x.x.37081: UDP, length 288

Source port 0/udp IP fragmentation

Sometimes we see reflection attacks showing UDP source and destination port numbers set to zero. This is usually a side effect of attacks where the reflecting servers responded with large fragmented packets. Only the first IP fragment contains a UDP header, preventing subsequent fragments from being reported properly. From a router point of view this looks like a UDP packet without UDP header. A confused router reports a packet from source port 0, going to port 0!

This is a tcpdump-like view:

$ tcpdump -n -r 4651d0ec9e6fdc8e.pcap -c 8

02:05:03.408800 IP - 190.88.35.82.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1167

02:05:03.522186 IP - 95.111.126.202.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1448

02:05:03.525476 IP - 78.90.250.3.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 839

02:05:03.550516 IP - 203.247.133.133.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1472

02:05:03.571970 IP - 54.158.14.127.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1328

02:05:03.734834 IP - 1.21.56.71.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1250

02:05:03.745220 IP - 195.4.131.174.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1472

02:05:03.766862 IP - 157.7.137.101.0 > x.x.x.x.0: UDP, length 1122

An avid reader will notice – the source IPs above are open DNS resolvers! Indeed, from our experience most of the attacks categorized as fragmentation are actually a side effect of DNS amplifications.

Source port 53/udp DNS

Over the last six months we’ve seen 253 DNS amplifications. On average an attack used 7100 DNS reflector servers and lasted 24 minutes. Average bandwidth was around 3.4Gbps with largest attack using 12Gbps.

This is a simplification though. As mentioned above multiple DNS attacks were registered by our systems as two distinct vectors. One was categorized as source port 53, and another as source port 0. This happened when the DNS server flooded us with DNS responses larger than max packet size, usually about 1,460 bytes. It’s easy to see if that was the case by inspecting the DNS attack packet lengths. Here’s an example:

DNS attack packet lengths min:44.00 avg:1458.94 max:1500.00 dev:208.14 count:40000

DNS attack packet lengths:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

8 | 0

16 | 0

32 | 129

64 | 479

128 | 84

256 | 164

512 | 268

1024 |************************************************** 38876

The great majority of the received DNS packets were indeed close to the max packet size. This suggests the DNS responses were large and were split into multiple fragmented packets. Let’s see the packet size distribution for accompanying source port 0 attack:

$ tcpdump -n -r 4651d0ec9e6fdc8e.pcap

| grep length

| sed -s 's#.*length ([0-9]+).*#1#g'

| ~/bin/mmhistogram -t "Port 0 packet length" -l -b 100

Port 0 packet length min:0.00 avg:1264.81 max:1472.00 dev:228.08 count:40000

Port 0 packet length:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

0 | 348

100 | 7

200 | 17

300 | 11

400 | 17

500 | 56

600 | 3

700 | ** 919

800 | * 520

900 | * 400

1000 | ******** 3083

1100 | ************************************ 12986

1200 | ***** 1791

1300 | ***** 2057

1400 |************************************************** 17785

About half of the fragments were large, close to the max packet length in size, and rest were just shy of 1,200 bytes. This makes sense: a typical max DNS response is capped at 4,096 bytes. 4,096 bytes would be seen on the wire as one DNS packet fragment with an IP header, one max length packet fragment and one fragment of around 1,100 bytes:

4,096 = 1,460+1,460+1,060

For the record, the particular attack illustrated here used about 17k reflector server IPs, lasted 64 minutes, generated about 6Gbps on the source port 53 strand and 11Gbps of source port 0 fragments.

We have blogged about DNS reflection attacks in the past:

- How to Launch a 65Gbps DDoS, and How to Stop One

- Deep Inside a DNS Amplification DDoS Attack

- How the Consumer Product Safety Commission is (Inadvertently) Behind the Internet’s Largest DDoS Attacks

Other protocols

We’ve seen amplification using other protocols such as:

- port 19 – Chargen

- port 27015 – SRCDS

- port 20800 – Call Of Duty

…and many other obscure protocols. These attacks were usually small and not notable. We didn’t see enough of then to provide meaningful statistics but the attacks were automatically mitigated.

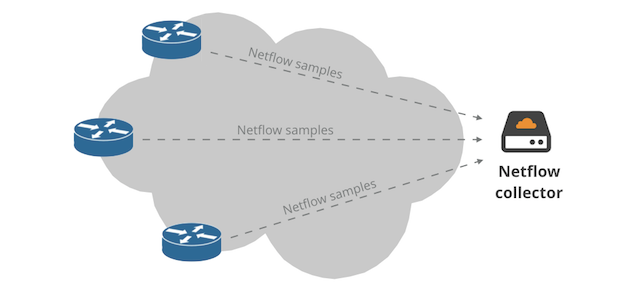

Poor observability

Unfortunately we’re not able to report on the contents of the attack traffic. This is notable for the NTP and DNS amplifications – without case by case investigations we can’t report what responses were actually being delivered to us.

This is because all these attacks stopped at the network layer. Routers are heavily optimized to perform packet forwarding and have a limited capacity of extracting raw packets. Basically there is no “tcpdump” there.

We track these attacks with netflow, and we observe them hit our routers firewall. The tcpdump snippets shown above were actually fake, reconstructed artificially from netflow data.

Trivial to mitigate

With properly configured firewall and sufficient network capacity (which isn’t always easy to come by unless you are the size of Cloudflare) it’s trivial to block the reflection attacks. But note that we’ve seen reflection attacks up to 80Gbps so you do need sufficient capacity.

Properly configuring a firewall is not rocket science: default DROP can get you quite far. In other cases you might want to configure rate limiting rules. This is a snippet from our JunOS config:

term RATELIMIT-SSDP-UPNP {

from {

destination-prefix-list {

ANYCAST;

}

next-header udp;

source-port 1900;

}

then {

policer SA-POLICER;

count ACCEPT-SSDP-UPNP;

next term;

}

}

But properly configuring firewall requires some Internet hygiene. You should avoid using the same IP for inbound and outbound traffic. For example, filtering a potential NTP DDoS will be harder if you can’t just block inbound port 123 indiscriminately. If your server requires NTP, make sure it exits to the Internet over non-server IP address!

Capacity game

While having sufficient network capacity is necessary, you don’t need to be a Tier 1 to survive amplification DDoS. The median attack size we’ve received was just 3.35Gbps, average 7Gbps, Only 195 attacks out of 6,353 attacks recorded – 3% – were larger than 30Gbps.

All attacks in Gbps: min:0.04 avg:7.07 med:3.35 max:78.03 dev:9.06 count:6329

All attacks in Gbps:

value |-------------------------------------------------- count

0 | **************** 658

1 | ************************* 1012

2 |************************************************** 1947

4 | ****************************** 1176

8 | **************** 641

16 | ******************* 748

32 | **** 157

64 | 14

But not all Cloudflare datacenters have equal sized network connections to the Internet. So how can we manage?

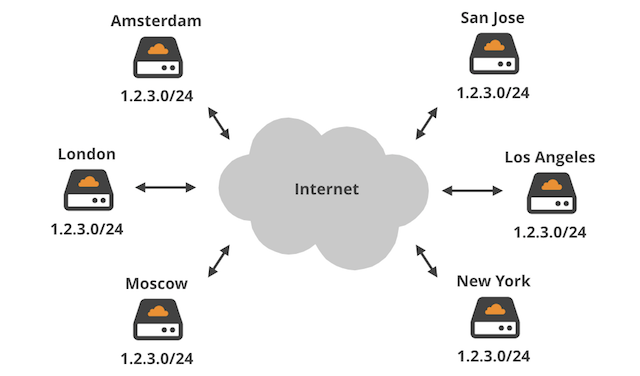

Cloudflare was architected to withstand large attacks. We are able to spread the traffic on two layers:

- Our public network uses Anycast. For certain attack types – like amplification – this allows us to split the attack across multiple datacenters avoiding a single choke point.

- Additionally we use ECMP internally to spread a traffic destined to single IP address across multiple physical servers.

In the examples above, I showed a couple of amplification attacks getting nicely distributed across dozens of datacenters across the globe. In the shown attacks, if our router firewall failed, our physical servers wouldn’t receive more than 500kpps of attack data. A well tuned iptables firewall should be able to cope with such a volume without a special kernel offload help.

Inter-AS Flowspec for the rest

Withstanding reflection attacks requires sufficient network capacity. Internet citizens not having fat network cables should use a good Internet Service Provider supporting flowspec.

Flowspec can be thought of as a protocol enabling firewall rules to be transmitted over a BGP session. In theory flowspec allows BGP routers on different Autonomous Systems to share firewall rules. The rule can be set up on the attacked router and distributed to the ISP network with the BGP magic. This will stop the packets closer to the source and effectively relieve network congestion.

Unfortunately, due to performance and security concerns only a handful of large ISP’s allow inter-AS flowspec rules. Still – it’s worth a try. Check if your ISP is willing to accept flowspec from your BGP router!

At Cloudflare we maintain an intra-AS flowspec infrastructure, and we have plenty of war stories about it.

Summary

In this blog post we’ve given details of three popular reflection attack vectors: NTP, SSDP and DNS. We discussed how the Cloudflare Anycast network helps us avoid a single choke point. In most cases dealing with reflection attacks is not rocket science though sufficient network capacity is needed and simple firewall rules are usually enough to cope.

The types of DDoS attacks we see from other vectors (such as IoT botnets) are another matter. They tend to be much larger and require specialized, automatic DDoS mitigation. And, of course, there are many DDoS attacks that occur using techniques other than reflection and not just using UDP.

Whether you face DDoS attacks of 10Gbps+, 100Gbps+ or 1Tbps+, Cloudflare can mitigate them.

No comments yet.