Typo traps: analyzing traffic to exmaple.com (or is it example.com?)

A typo is one of those common mistakes with unpredictable results when it comes to the Internet’s domain names (DNS). In this blog post we’re going to analyze traffic for exmaple.com, and see how a very simple human error ends up creating unintentional traffic on the Internet.

Cloudflare has owned exmaple.com for a few years now, but don’t confuse it with example.com! example.com is a reserved domain name set by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), under the direction of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It has been used since 1999 as a placeholder, or example, in documentation, tutorials, sample network configurations, or to prevent accidental references to real websites. We use it extensively on this blog.

As I’m writing it, the autocorrect system transforms exmaple.com into example.com, every time, assuming I must have misspelled it. But in situations where there’s no automatic spelling correction (for example, while editing a configuration file) it’s easy for example to become exmaple.

And so, lots of traffic goes to exmaple.com by mistake — whether it was a typoed attempt to reach example.com or due to other random reasons. Fake email accounts in marketing forms are among these reasons (more details below). This phenomenon of “typosquatting” is used by attackers hoping someone misspells the name of a known brand, as we saw in March in our blog “Top 50 most impersonated brands in phishing attacks and new tools you can use to protect your employees from them”. Random typos that cause networks (big or small) problems have also been around for a while.

Here is what the example.com web page shows to a user who goes directly to that domain name:

And this is what exmaple.com looks like:

A bit of exmaple.com history

exmaple.com came to us a few years ago from a customer. He registered the domain to prevent malicious exploitation, but got tired of dealing with more traffic than expected — it’s not the first time that this has happened (icanhazip.com was another similar example). Too much traffic does come at a financial cost. So, why would a domain name like exmaple.com, that is not promoted anywhere, have traffic? It shows how unintentional traffic is a real thing with the right domain name. It could also be a result of a typo in network configurations or a misconfigured router, as we’re going to see next.

Let’s explore, then, what traffic goes to exmaple.com by answering some questions.

How much traffic does it get?

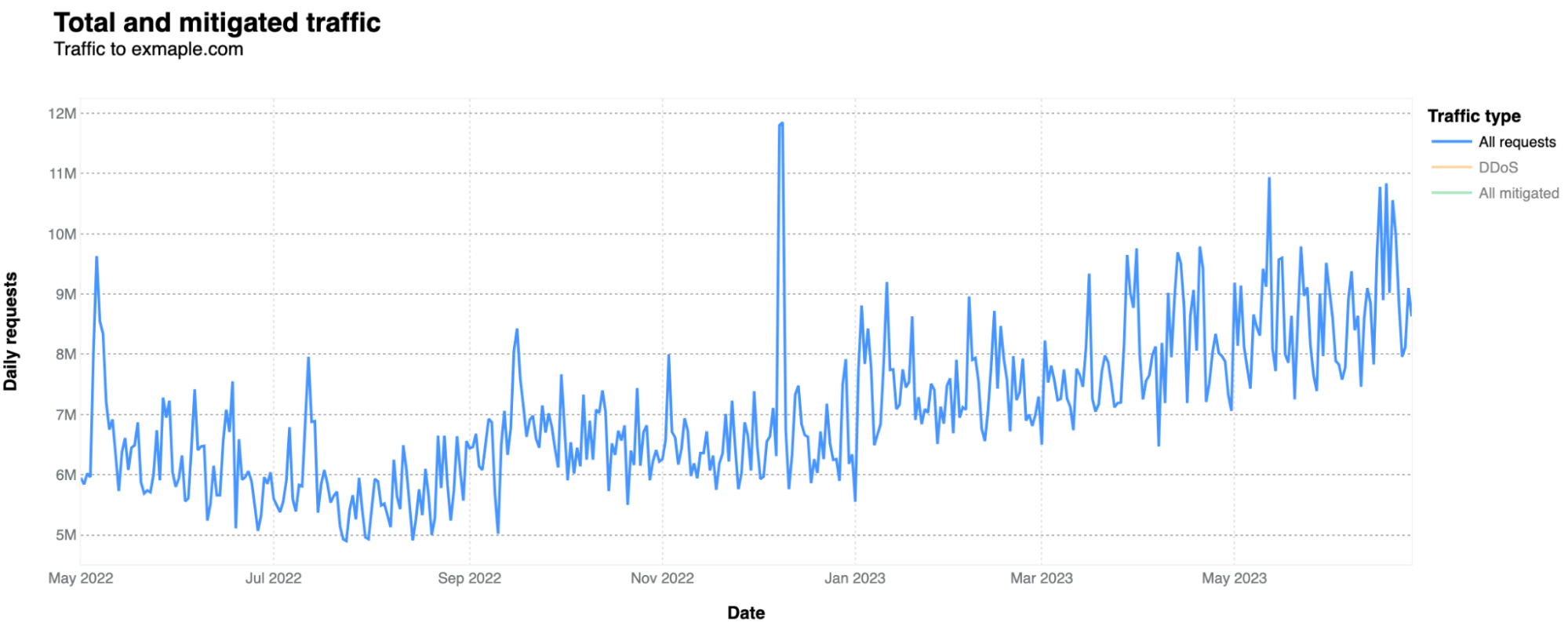

It gets much more traffic than one would expect in terms of HTTP requests, given that it is mostly used because someone or a system/router set by someone, misspelled example.com. In terms of bytes, the numbers are minimal, as this is a very simple site with only a short text sentence, as shown above. Usually, on a daily basis, it doesn’t go over 1 Mbps. In a 12-month period (May 2022-June 2023), it had 2.48 billion HTTP requests, but it has been increasing over recent months. In April 2023, it was 243 million requests, an 8.13 million daily average, against a 6.07 million daily average in June 2022.

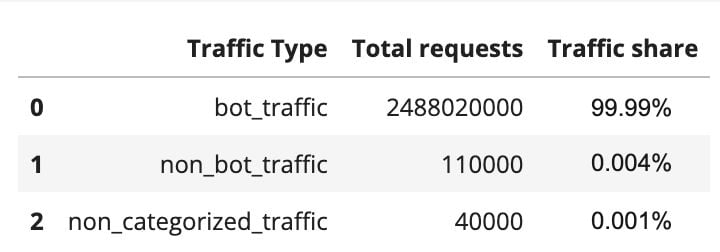

What type of traffic is it? Almost all HTTP traffic that goes to exmaple.com is categorized as bot-related. That’s around 99.99%: 2.48 billion requests were from bots, 110,000 were not from bots, and 40,000 we weren’t able to categorize. This already gives us some information, showing that the majority of traffic is not a typical user simply adding exmaple.com by mistake to some documentation or tutorial. This is mostly automated traffic (more on that below).

There are also a few peaks worth mentioning. There’s a clear spike in bot traffic on December 8 and 9, 2022 (11.8 and 11.85 million requests, respectively), the week after Cyber Monday week.

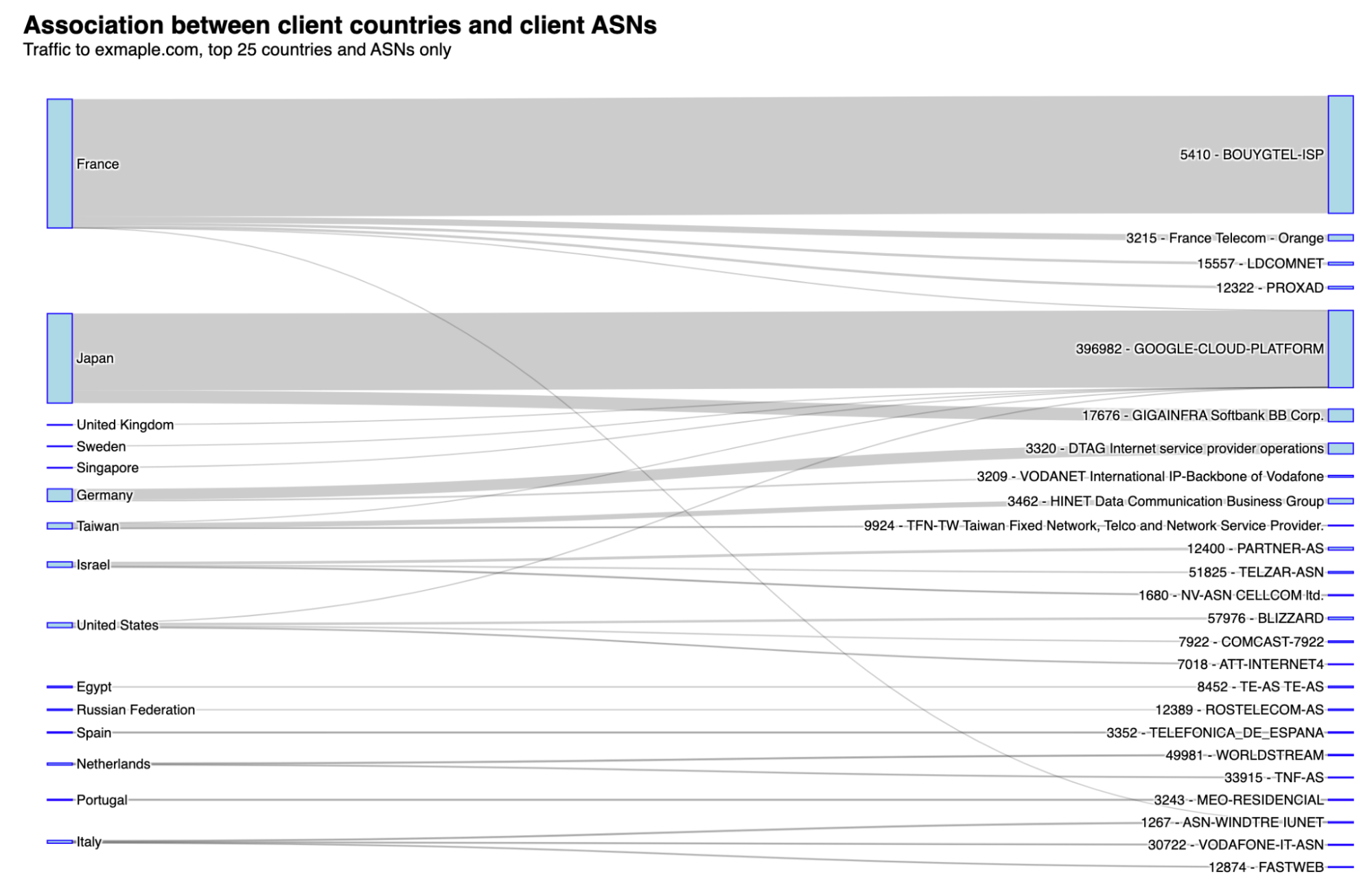

From which countries are requests coming from? The top countries include France, Japan, Germany, and the US. Below, we’re going to check why this happens by looking at the autonomous system (ASNs) perspective. Never forgetting that connected networks or AS’s make up the Internet.

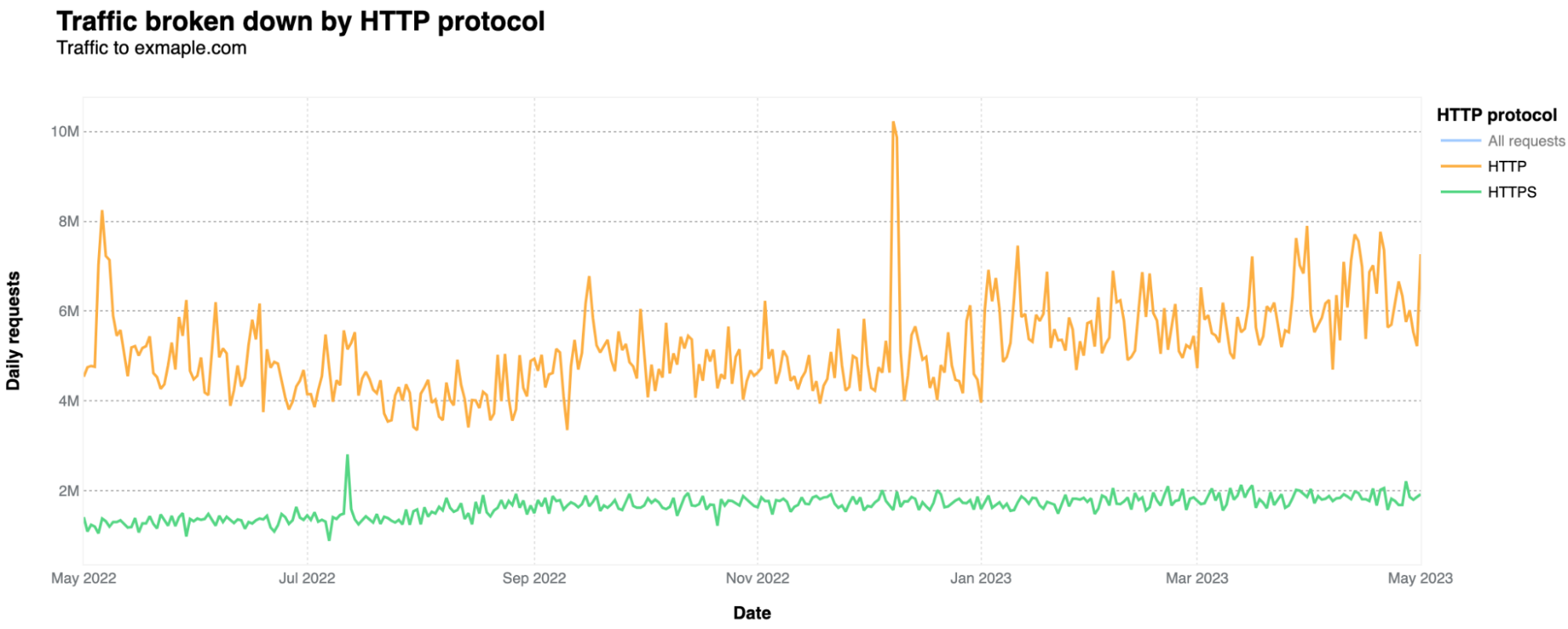

How about HTTP protocols?

In terms of the HTTP protocols, the majority uses unencrypted HTTP only, accounting for 76% of all requests, while HTTPS represents 24%. That is actually unusual in the modern day Internet. As Cloudflare Radar data shows, excluding bots, HTTPS represents 99.3% of all requests in a general Cloudflare perspective, and its 80.8% of HTTPS for bots-only traffic. HTTPS adds a layer of security (SSL/TLS encryption), ensuring data remains confidential.

HTTP is definitely more used by automated traffic, given that HTTPS is more used for human consumption, as browsers tend to prioritize HTTPS. Only 6% of human-related requests use HTTP (the rest is HTTPS). That HTTP percentage jumps to 76%, when considering automated requests-only.

Is exmaple.com the target of cyber attacks?

The short answer is yes. But it’s a very low percentage of requests that are mitigated. The biggest spike in application layer attacks was on December 9, 2022, with 560k HTTP daily requests categorized as DDoS attacks. Nothing of large scale, but that said, small attacks can also take down under-protected sites. WAF mitigations had a 10k spike on November 2, 2022.

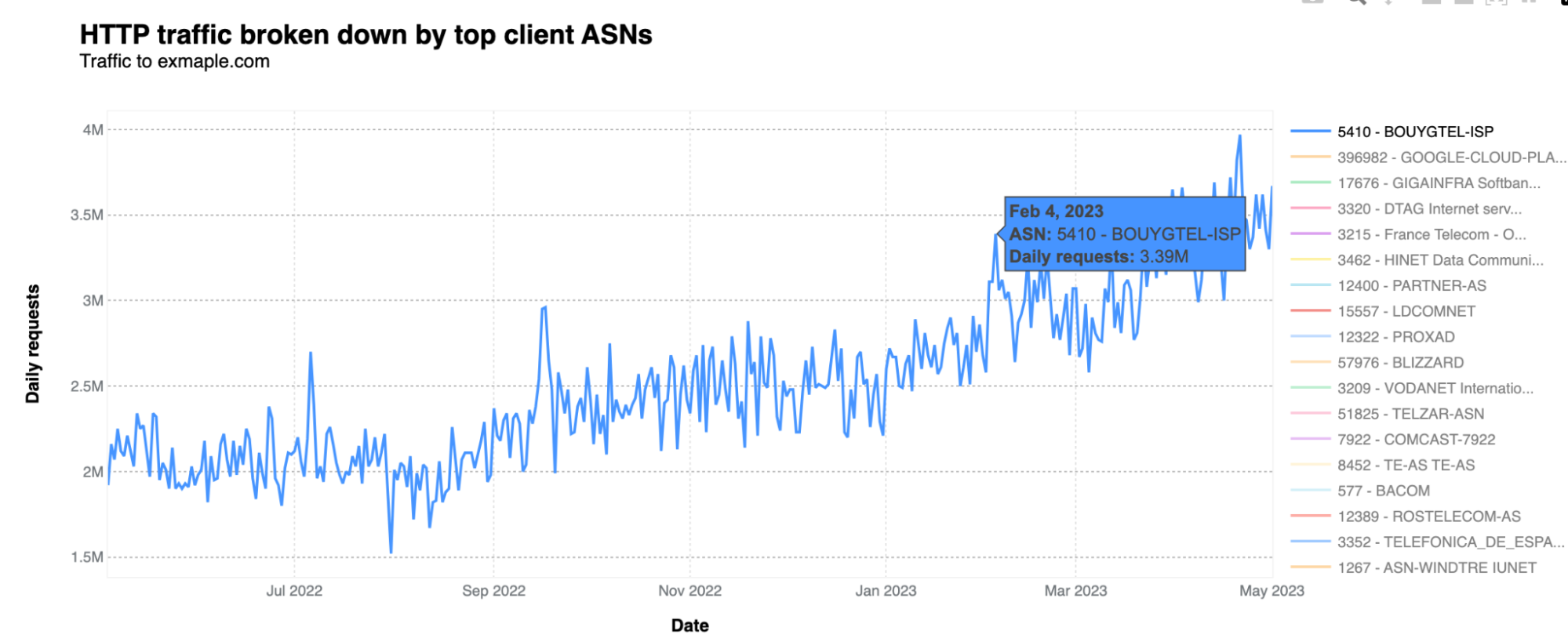

Generating the most traffic: a French ISP

What drives most of the traffic are very specific ASNs. In this case, the dominant one is one of France's main Internet operators, Bouygues Telecom. Its AS5410 is generating the most traffic to exmaple.com, followed by Google Cloud, in Japan. Bouygues Telecom traffic to exmaple.com means more than three million daily requests at least since February 2023. Here’s the AS5410 over time traffic:

We contacted Bouygues Telecom to let them know a couple of weeks ago, and shared information about where we were seeing traffic from. So far, they haven’t found the needle in the haystack sending traffic to exmaple.com, potentially related to some erroneous configuration.

And since, exmaple.com is not a malicious site, so there’s no harm, no foul. However, one could wonder what might happen if this were a malicious domain. Identifying and resolving misconfigurations is important for network administrators to ensure efficient and secure network operations.

There are a few other ASN-related oddities. A major spike in traffic on December 8, 2022, with 5.84 million HTTP requests on a single day, came from the Netherlands-based AS49981, Worldstream (an Infrastructure-as-a-Service provider). And on March 28-29, 2023, it was Russian Rostelecom AS12389, with a double spike of around 1.8 million requests per day. On June 18, 2022, it was German Deutsche Telekom AS3320, and on May 6, 2022, there was a 2.31 million HTTP requests daily spike from Bell Canada’s ISP, AS577, just to mention those with clearer spikes.

Here is the list that associates countries with the ASNs that are generating more traffic to exmaple.com:

Why does this happen in specific ASNs in different regions of the world, you may ask? Even without a definitive answer, the amount of daily traffic from those ASNs, and the prevalence of bot traffic, seems to indicate that most traffic is related to a possible misconfiguration in a router, software or network setting, intended to go to example.com.

As we observed previously, example.com is used for testing, educational, or illustrative purposes, including in routers from specific networks. It could be for network troubleshooting and testing, training, simulations, or it also could be in the documentation or guides for configuring routers, as examples to illustrate how to set up DNS configurations, route advertisement, or other networking settings.

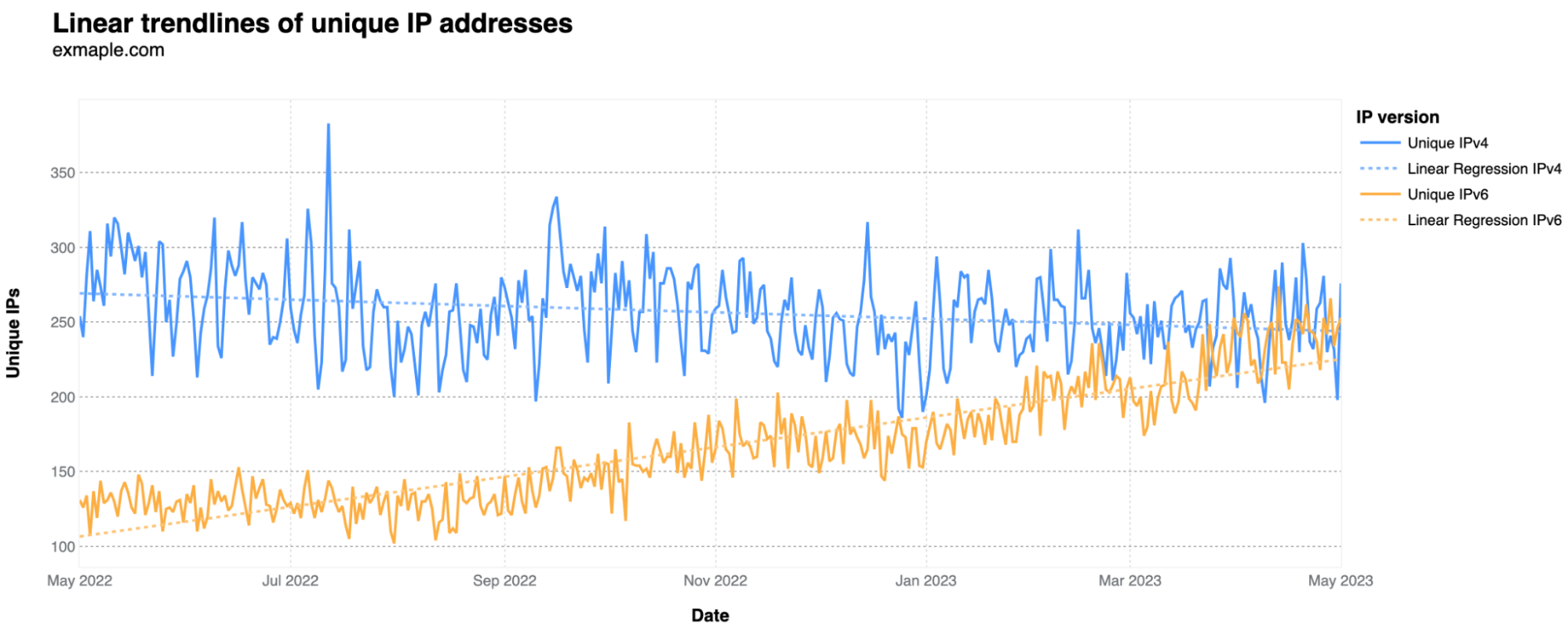

What are the main IP versions and browsers?

Regarding IP versions, they can be IPv4 or IPv6 — v6 emerged as a solution when the initial v4 wasn't prepared for the Internet's growth. For exmaple.com unique visitors, looking at the daily number of unique IPs where requests originate, IPv6 has been rising in comparison to IPv4. This suggests that IPv6 is now more frequently used by the services and bots generating most of this traffic. It started in May at 30% IPv6 usage and is now around 50%.

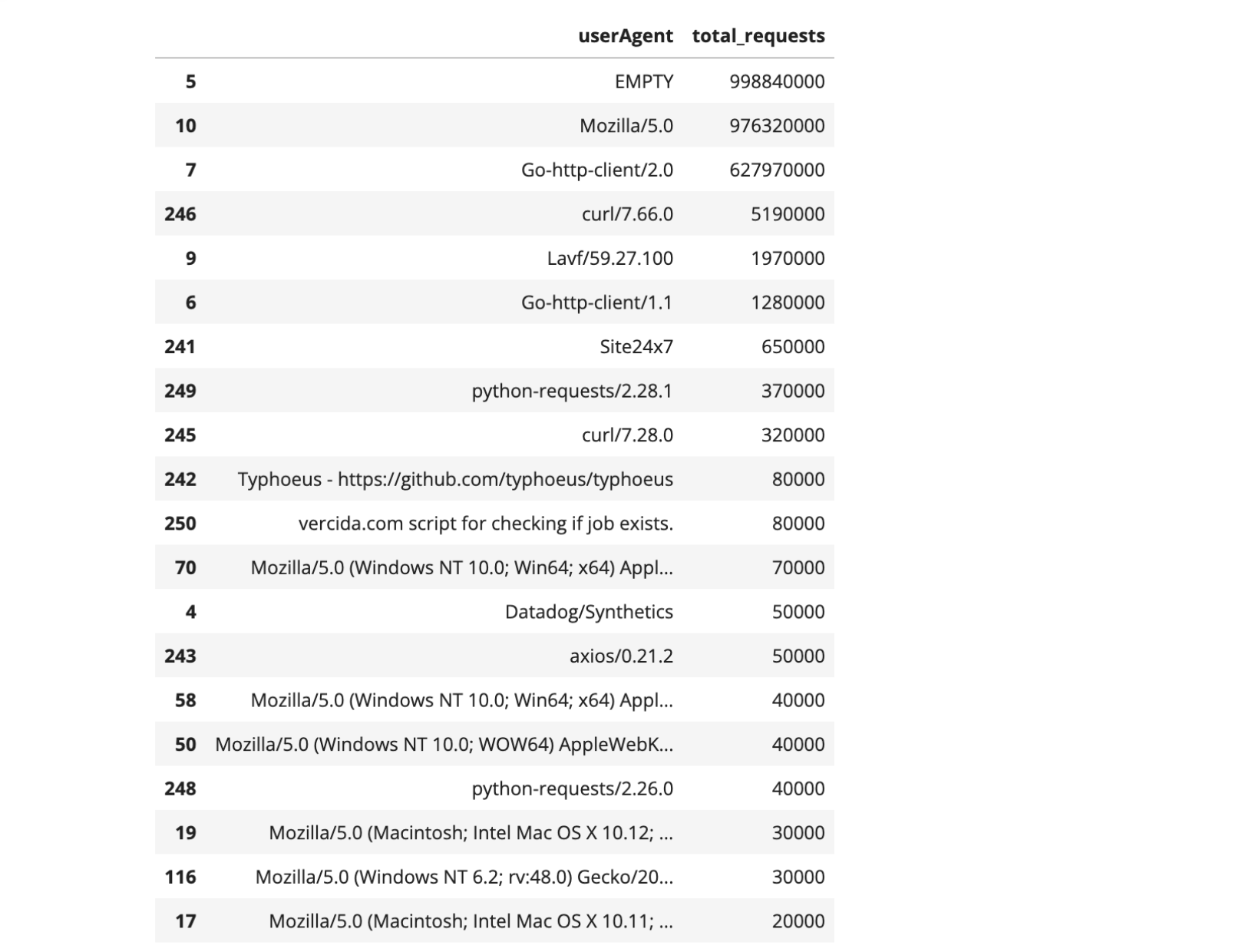

The user-agent header sent by the visitor's web browser in the HTTP request typically contains information about the used browser, operating system, and sometimes even the device. But in this case, the user-agent information doesn’t give us much detail, even of there’s some odd ones. “Empty” (when user agents are absent) comes first, followed by “Mozilla/5.0” and “Go-http-client/2.0”. What do those user-agents mean?

- The user agent string “Mozilla/5.0” is widely used by a variety of web browsers, both mainstream and niche, including Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, and Opera. Therefore, it is challenging to attribute the usage of “Mozilla/5.0” specifically to a single browser or user category. While “Mozilla/5.0” is associated with legitimate browsers, it's worth noting that user agent strings can be easily manipulated or forged by bots and malicious actors.

- “Go-http-client/2.0” indicates that the request is coming from a program or application written in the Go programming language (often referred to as Golang).

There are also a few others represented with known meanings, such as “curl/7.66.0” (the numbers correspond to the specific version being used). This user agent string indicates that the HTTP request was made using the cURL command-line tool, a popular tool used for tasks like downloading files, automated testing, debugging, or server monitoring. There’s also “Lavf/59.27.100”, a less common user agent tied to FFmpeg's Lavf library for multimedia tasks, and “python-requests/2.28.1”, that indicates the use of the Python Requests library, popular for sending HTTP requests and interacting with web services.

In the camp of more unusual user agents, with a few thousand requests, are instances like a specific GitHub page (a software library called Typhoeus) or a possible “script for checking if job exists” for the job searching site vercida.com.

From where did the users access the website? Let's examine the distribution of HTTP referrers. Note that the term “referer” is based on a misspelling in the original specification that has persisted (it should be “referrer header” instead) in HTTP — in the original HTTP proposal Tim Berners-Lee spells it “referrer” as well. The referer or referrer header is an optional field that provides information about the URL of the web page from which a particular request originated.

The predominant “referer” used is “empty”, which occurs when a user agent isn’t provided, also possibly meaning direct access or by bookmark. Next is exmaple.com itself (an unusual pattern, given there are no links on exmaple.com), with a peak of 160,000 requests on February 6, 2023. Following that is a curious spike of 10,000 requests from “reddit.com” on January 30, 2023, possibly due to a misspelling of example.com in a Reddit post that got popular.

We didn’t find a specific Reddit post from January 30 mentioning exmaple.com, but there were a few there over the years, clearly aiming to show example.com. Some of those are as recent as one year or even 10 months, like this Reddit post on the AWS subreddit, or this one from January 31, 2023, related to SEO.

On that note, regarding human misuse of misconfigurations impacting the Internet, in 2018, a member of the Cloudflare team gave a presentation about “Internet Noise” during a RIPE event that can be consulted here. It’s about unwanted traffic due to misconfigurations and misuse of proxies and internal use situations.

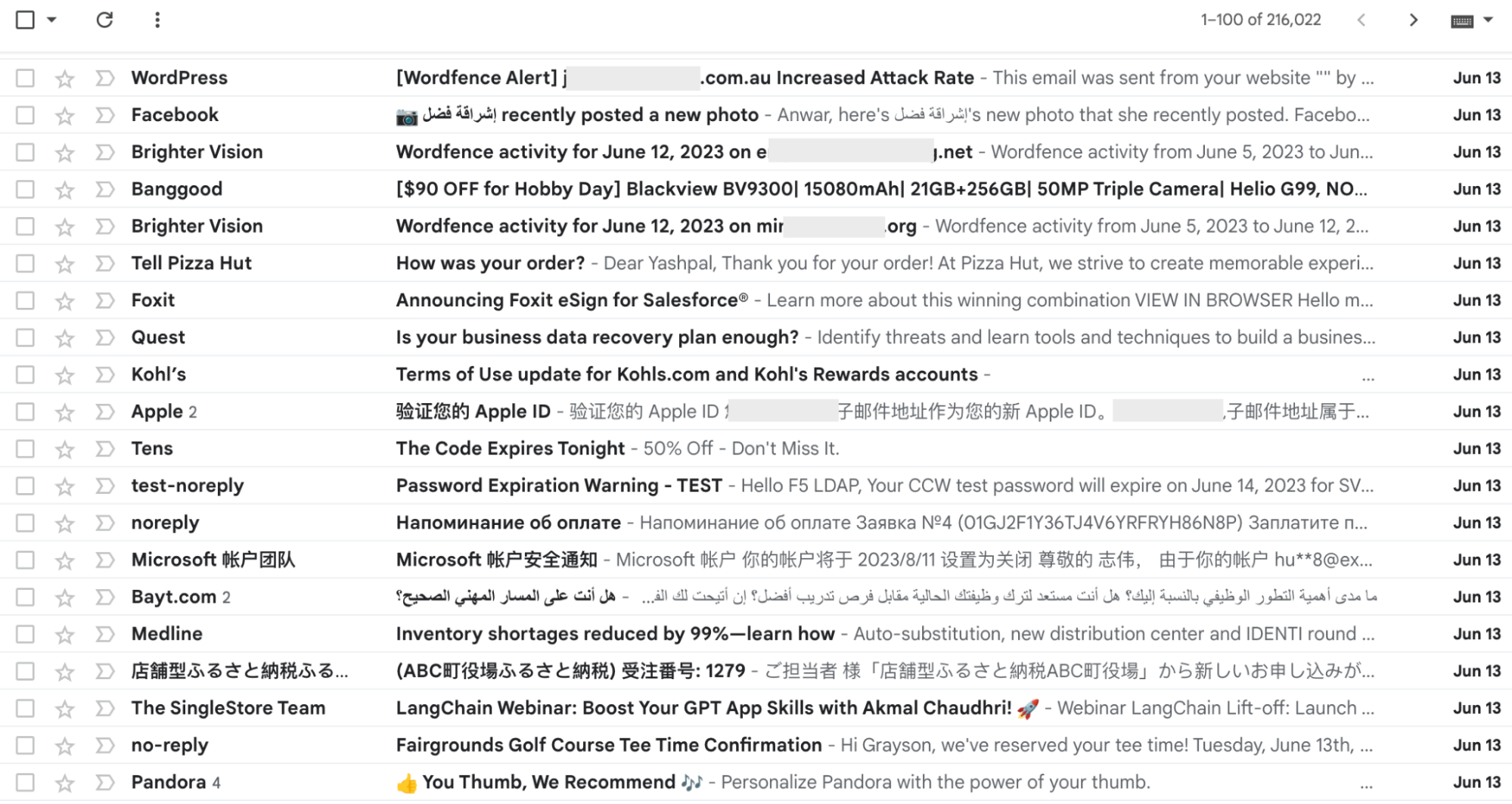

How about exmaple.com email trends?

Although no email address online intentionally targets exmaple.com, that address still gets some email attention. We configured a Gmail account to monitor these random emails in early 2022. Within 16 months, the 15 GB email capacity was fully used, containing 216,000 emails — an average of 432 daily emails. These emails reflect various scenarios: some are marketing-related, others appear to be network tests, and some are from individuals who, by error or to avoid spam, ended up at “@exmaple.com”. Among these use cases, we noticed accounts linked to PlayStation, Apple devices, Pandora music, Facebook, and more.

Examining a 30-day span of emails (late July to late August), we noticed that certain types of emails are more common than others. This is notably seen in tests conducted by computer software applications that monitor systems, networks, and infrastructure. The main example of this is Nagios.

Since late July, nearly 83% of almost 4,000 emails were from Nagios. The sender used a “local domain” from Nagios, and the email address was “test@exmaple.com”—where example.com was likely the intended recipient. The subjects alternated between “PROBLEM Service Alert: [Name of company] ATM/PING is WARNING” and “RECOVERY Service Alert: [Name of company]_Backup/PING is OK”, indicating service tests.

Analyzing the regions where most emails originate (based on our data centers), it's evident that North America and Southeast Asia are the primary sources, along with Europe. Regarding languages, English dominates, but some emails are in German, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, Thai, and Russian.

Microsoft (56 emails), Apple (30), and Google (20 emails) are in the mix. Surprisingly, emails from various golf courses (31 emails from eight different golf courses) were also present, along with emails from cruise ship companies. Additionally, there are emails from well-known brands such as Call of Duty, PlayStation, HP, Uber (related to Uber Eats), McAfee, and even the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (in newsletter subscription emails) that were observed (in this case, from the actual brands and not spam look alike). While Facebook-related emails were present in previous months, they haven't been seen recently.

Some emails clearly reveal their “fake” email intent, like “fakename@exmaple.com”, sent by a virtual learning platform, likely when someone provided a randomly false email address. There are also repeated instances of people’s names like Mike or others, including surnames, before “@exmaple.com”. This suggests that people use the same fictitious email address when asked for their email by companies.

Here are some of the most creatively formed or interesting email addresses provided between July and August 2023, organized by us based on types of chosen email addresses (we included the number of emails in the most frequently used ones):

.tg {border-collapse:collapse;border-color:#ccc;border-spacing:0;}

.tg td{background-color:#fff;border-color:#ccc;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;color:#333;

font-family:Arial, sans-serif;font-size:14px;overflow:hidden;padding:10px 5px;word-break:normal;}

.tg th{background-color:#f0f0f0;border-color:#ccc;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;color:#333;

font-family:Arial, sans-serif;font-size:14px;font-weight:normal;overflow:hidden;padding:10px 5px;word-break:normal;}

.tg .tg-0lax{text-align:left;vertical-align:top}

| han.solo@exmaple.com — our favorite | yes@exmaple.com — 35 emails |

|---|---|

| you@exmaple.com — 20 | mike@exmaple.com — 25 |

| example@exmaple.com — 17 | exampe@exmaple.com |

| example1@exmaple.com | exmaple@exmaple.com |

| johnsmith@exmaple.com | fakename@exmaple.com |

| fake@exmaple.com | fu??off@exmaple.com — (we removed two letters for obvious reasons) |

| test@exmaple.com — 3200 (used by a software company) | testing@exmaple.com |

| testtest.soneda@exmaple.com | abctest@exmaple.com — 11 |

| testtm@exmaple.com | tester@exmaple.com |

| test59472@exmaple.com | asdfsdafasfasfd@exmaple.com |

| DNA@EXMAPLE.COM | garanhao@exmaple.com |

| ngduykhang2703@exmaple.com | fgklfjdhkghfdkjgh@exmaple.com — 5 |

| asdfzxcvadfas@exmaple.com | hdhdhxh@exmaple.com |

| youmane@exmaple.com | youremail@exmaple.com |

| yourname@exmaple.com | yournanme@exmaple.com |

| otro@exmaple.com | other@exmaple.com |

| person@exmaple.com | someone@exmaple.com |

| student@exmaple.com | ronaldo@exmaple.com |

| ruth+notwaived@exmaple.com | sample@exmaple.com |

| user4@exmaple.com | email@exmaple.com — 20 |

| ggg@exmaple.com | ame@exmaple.com |

| me@exmaple.com — 14 | hellouser@exmaple.com |

| localuser@exmaple.com | user@exmaple.com |

| user2@exmaple.com | username12@exmaple.com |

| iam_beautiful@exmaple.com — 15 | lovelyxcookies749@exmaple.com |

| ninfo@exmaple.com | no-reply@exmaple.com |

| Noreply@exmaple.com | nobody@exmaple.com — 10 |

| alex.test@exmaple.com | d@exmaple.com |

| goodguy@exmaple.com | 123@exmaple.com |

| 999@exmaple.com | 0491087030@exmaple.com |

| a@exmaple.com | random@exmaple.com |

| noemail@exmaple.com | Noemail221@exmaple.com |

| contact@exmaple.com | daufrecht@exmaple.com — (“daufrecht” means upright in German) |

| willshippingwork@exmaple.com | niemail@exmaple.com |

| examiner@exmaple.com |

Email authentication. DMARC and friends

In the realm of email, DMARC (that stands for “Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance”) is a security protocol that helps prevent email spoofing and phishing attacks by providing a framework. It is used by email senders to authenticate their messages and receivers to verify their authenticity. DMARC is based on both SPF (verifies if an email was sent by an authorized sender) and DKIM (the receiving server will check the DKIM-Signature header), and the domains used by those two protocols. So, DMARC requires that SPF or DKIM “pass”.

The implementation of DMARC signals that an email sender is taking measures to improve email security and protect their domain's reputation. With this context, let’s delve into DMARC validation. How did these random email senders to “@exmaple.com”? Only 11% (433) of all emails (3890) from the past 30 days passed the DMARC authentication successfully, most of those were from recognized senders like Apple, Uber, or Microsoft.

This is also because a significant 83% (3252) of emails originated from what appear to be tests conducted by computer software applications that monitor systems, networks, and infrastructure — specifically, Nagios. All of these emails are categorized as “none” in terms of DMARC policies, indicating that the sender is not using a DMARC policy. This approach is frequently adopted as an initial phase to gauge the impact of DMARC policies before adopting more robust measures. Just 1% of all emails “failed” DMARC authentication, implying that these emails didn't align with the sender's designated policies.

In such instances, domain owners can instruct email providers to take actions such as quarantining the email or outright rejection, thus shielding recipients from potentially malicious messages. This was evident in domains like amazon.co.jp or sanmateo.flester.com (where “Undelivered Mail Returned to Sender” messages originated from the Mail Delivery System).

Our email perspective could have been even more comprehensive if this “@exmaple.com” email account had Cloudflare Area 1 — our cloud-native email security service that detects and thwarts attacks before they reach user inboxes. Perhaps in a future geeky venture, we will also incorporate that viewpoint, complete with percentages for spam, malicious content, and threat categories.

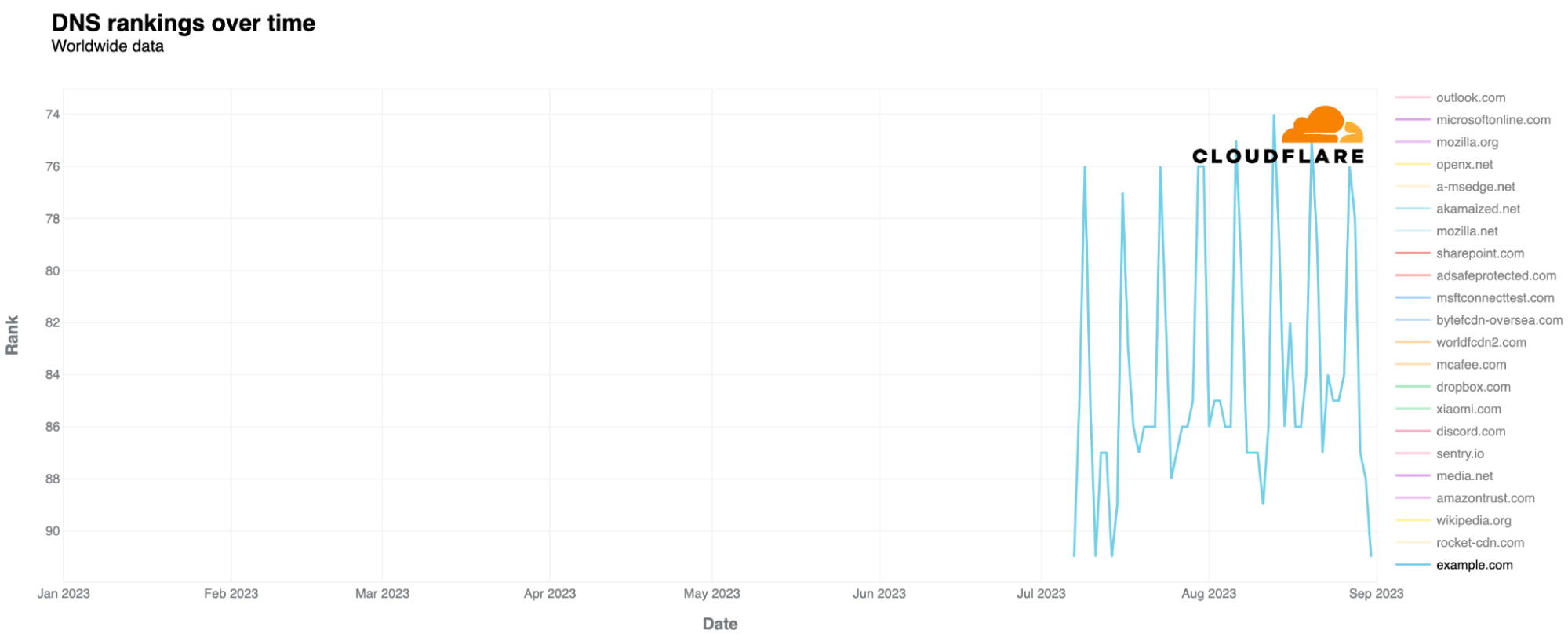

Where is example.com on our domain popularity ranking? What about exmaple.com?

Last but not least, we also have insight into example.com itself. Looking at our most popular domains list (using data from our 1.1.1.1 resolver), example.com or “example.org” are no strangers to our popular domains ranking. Those two are usual “guests” of our top 500 domains ranking, both worldwide and in specific countries, which also is an expression of its popularity and usage for all the use cases we already discussed. example.com usually sits higher, in the top 300. Since July, it has even appeared in our top 100 for the first time in 2023.

exmaple.com, on the other hand, is not in our top 100 list, and only appears in our top 100k top domains list. You can find our domains lists, including a top 100, and unordered CSV lists up to Top 1 million domains, on Cloudflare Radar and through our API.

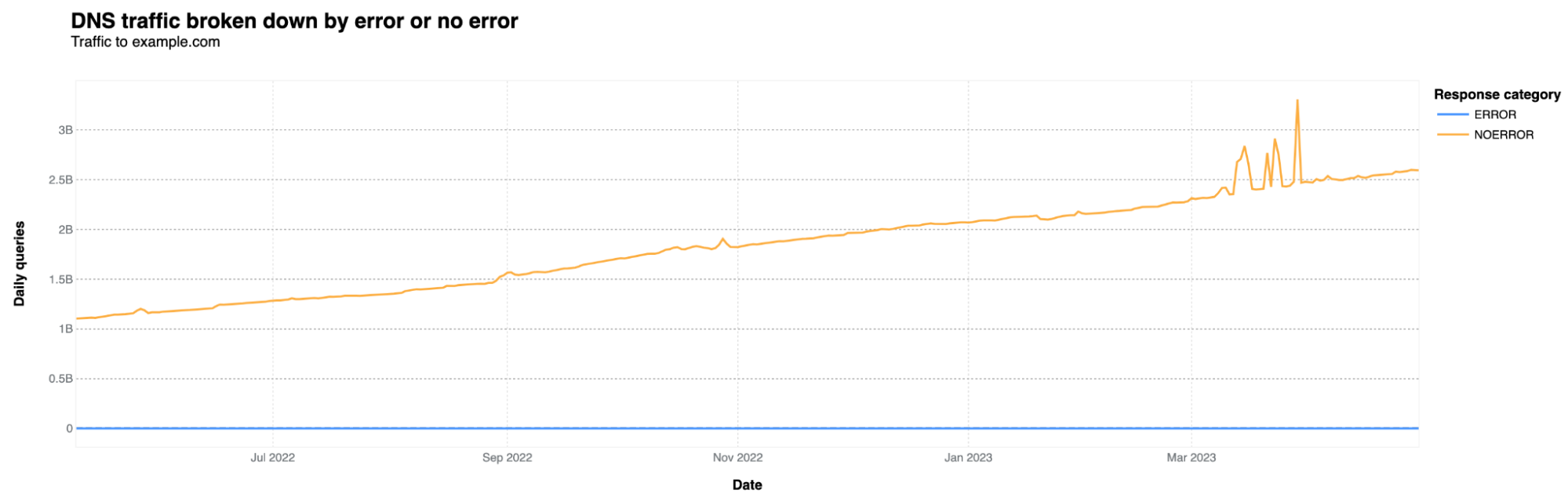

Just by checking DNS data from those who use our resolver, the original example.com gets around 2.6 billion DNS queries every day. This number has been consistently increasing since 2022, more than doubling. Here's the chart to show it:

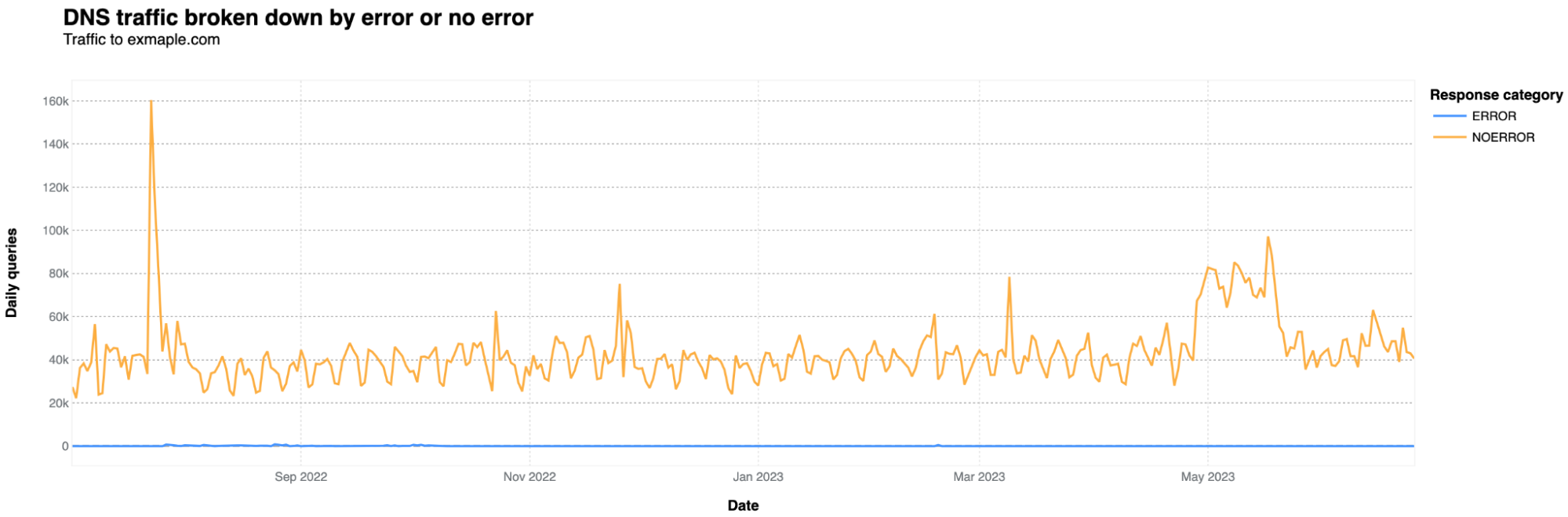

What about exmaple.com? DNS queries are significantly lower by an order of magnitude. On average, it receives around 40,000 DNS queries per day, with occasional spikes reaching 80,000 to 90,000 — there’s one 160k July 23, 2022, spike. It's also noteworthy that there are more DNS queries on weekdays and fewer on weekends, which is not the case for example.com.

Conclusion: Errare humanum est

“Some of the worst problems that happen on the Internet are not because somebody deliberately caused the problem. It’s because somebody made a mistake. We’ve lost half the networks ability to transport traffic or route it to the right destinations because somebody made a configuration mistake”.

— Vint Cerf, American Internet pioneer, in a 2016’s article: Vinton G. Cerf: Human error, not hackers threaten Net.

Even if traffic to exmaple.com arrives without consequences, a typo from a technician in a device for the wrong and malicious domain, could definitely have a negative impact if protections are not put in place. The typical Internet user is also susceptible to sending emails to the wrong address due to typos or could be tricked by domains resembling popular brands, but with errors.

Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome Lucius Seneca stated two thousand years ago, Errare humanum est or in plain English: to err is human. This held true for humans in the year AD 30 and remains so for humans in 2023. And the Internet, the complex network of networks that has grown larger than even its human inventors anticipated, is no stranger of these human errors, and its consequences. Quoting once again from Vint Cerf, “we need to have much better tools for writing software to avoid some of those stupid mistakes that cause problems in the Internet”.

After all this geeky analysis, my autocorrect finally recognizes “exmaple.com” and doesn't change it to “example.com”. Success.

(Thanks to Jorge Pacheco, Sofia Cardita, Jérôme Fleury, and Marek Majkowski for their contributions to this blog post.)